– MR Online

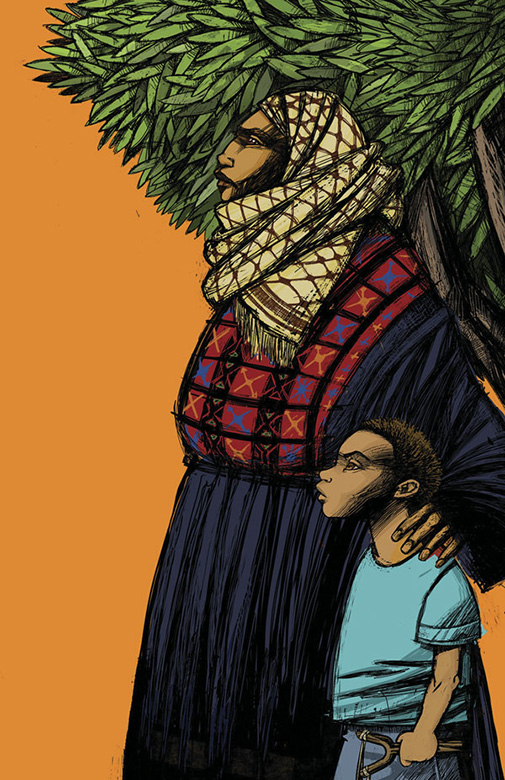

Pablo Kalaka (Chile and Venezuela), Under the Olive Tree, 2023. [Courtesy of Utopix and Artists Against Apartheid.]

Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

In the United Nations’ Humanitarian Situation Update #340 on the Gaza Strip (12 November 2025), there is a section on the distress experienced by more than 1 million Palestinian children in Gaza. The most common symptoms among children reported in the assessment are ‘aggressive behaviour (93 per cent), violence toward younger children (90 per cent), sadness and withdrawal (86 per cent), sleep disturbances (79 per cent), and education avoidance (69 per cent)’. Children account for about half the population in Gaza, where the median age is 19.6 years. They will struggle for a very long time to overcome these symptoms. There is no end in sight to the concrete conditions that produce them, namely the ongoing genocide and occupation.

Children face extraordinary attacks by the Israeli forces, some of which were documented in a recent report by Defense for Children International. For instance, on 22 October 2025, sixteen-year-old Saadi Mohammad Saadi Hasanain and a group of other children went to Saadi’s destroyed home to collect some of his belongings and firewood. Israeli quadcopters opened fire on them, forcing the children to scatter. Two of the boys escaped the attack; Saadi and another boy could not. The next morning, Saadi’s family found the body of the other boy, his head crushed. Beside him they found Saadi’s phone, his shoes, and his pants. Saadi’s shirt was tied around the body of the murdered boy. There is no news of Saadi, and his family fears he has been taken by Israeli forces.

Ilga (Palestine and Chile), Palestina resiste (Palestine Resists), 2016. [Courtesy of Utopix.]

Our latest dossier, Despite Everything: Cultural Resistance for a Free Palestine, includes a powerful line from the eighteen-year-old Gazan artist Ibraheem Mohana, who came of age during the genocide: ‘They started the war to kill our hopes, but we won’t let that happen’. We won’t let that happen. That refusal is a powerful sensibility.

The title of the dossier references the words of Palestinian actor and filmmaker Mohammad Bakri—despite everything, including the genocide, Palestinian culture will endure and will flourish. Not only will Palestinian culture survive the genocide, but it is the people’s cultural resources that will help heal the children and provide them with a pathway back to some level of sanity. Art is a safe refuge, a practice that allows a people to manage trauma that cannot be assimilated into their collective life. The trauma imposed on Palestinians is not necessarily an event but a process, a total way of life. Palestinian life, in fact, is marked by trauma. Art is a refuge from such trauma. No wonder that so many children who survive war and its afflictions on the body and mind can find a measure of healing through the therapy of art.

Kael Abello (Venezuela), Símbolos de resistencia (Symbols of Resistance), 2024. [Courtesy of Utopix.]

A few years ago, in Palestine, I got into a conversation with some artists about the role of art amongst a people engaged in a struggle for freedom. The main theme of our discussion was whether all Palestinian art should be about the occupation or whether it could be about other things. The consensus among us was that Palestinians are not under any obligation either to humanise themselves to those who are complicit in the occupation or to only produce art about the occupation. ‘Why can’t the artist make art for their own pleasure or for those who enjoy the art or to show that we can survive in the face of obliteration?’, asked Omar, a young artist from Jenin.

Art can be a refusal to be erased, a testimony against imperialist narratives, and an attempt to keep historical memory alive. ‘Whatever I can use to protect myself—paintbrush, pen, gun—they are tools of self-defence’, wrote the late Palestinian novelist and militant of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine Ghassan Kanafani. Palestinian artists pointed out that South Africans produced murals, music, poetry, and theatre as part of the anti-apartheid struggle (which we documented in our dossier on the Medu Art Ensemble). The imprint of the fight for human dignity is not only present on the battlefields of national liberation but equally in the hearts of the people who aspire to win their freedom, even as others seek to deny them that right. The struggle of the oppressed to win their freedom is a struggle to vitalise cultural resources into a democratic force of their own.

Aude Abou Nasr (Lebanon), Gaza, 2023. [Courtesy of Artists Against Apartheid.]

Hanan Wakeem, lead vocalist of the band Darbet Shams (Sunstroke), told Tings Chak in an interview for the dossier that in the early months of the genocide she and other Palestinians ‘were marked by total shock. Many artists couldn’t sing, move, or create’. ‘There were constant questions about the role of art in a time of genocide’, she added. ‘Is it appropriate to make music at all? If the song isn’t about the war, should it even be shared?’ Such questions linger, repeating over and over again when space and time crumble into a genocide.

Just before the genocide began, Darbet Shams released a song called ‘Raqsa’ (رَقْصة), meaning ‘dance’. The lyrics are sublime:

Feet rooted in the earth,

a head lifted to the stars.

Eyes that make sorrow sway,

a heart etched in sunlight.Living on the breath that sustains us,

to kindle paths gone dim.

A thought shaped by people’s gaze,

a smile hiding its grief.It stirs the story living in us

and fills it with heroes.We breathe a melody into the earth’s ribs

and fashion a homeland that reflects who we are.

I was thinking about this song when I read the dossier, thinking about how powerfully poetic and political it remains—even anticipating a genocide that seems to be the permanent condition of the Palestinian people since 1948.

Olfer Leonardo (Peru), Sabra y Shatila (Sabra and Shatila), 2021. [Courtesy of Utopix.]

Since 7 October 2023, Israeli bombs have fallen on the sites of Palestinian social reproduction (bakeries, fishing boats, agricultural fields, homes, hospitals) and institutions of Palestinian cultural life (universities, galleries, mosques, and libraries). One of these institutions is the Edward Said Public Library in northern Gaza, which attracted dozens of visitors every day. The poet Mosab Abu Toha founded the library in 2017 and, in 2019, decided to raise money for a second branch in Gaza City which had a computer lab where children and adults could learn to use computer programmes and design websites.

In November 2023, the Israelis bombed the Gaza Municipal Library. Over the following months, they also bombed Gaza’s public universities, destroying their libraries. By April 2024, thirteen public libraries had been erased. The destruction of libraries in Gaza led to the formation of Librarians and Archivists with Palestine, which has worked to document the ruin. A few months later, the Israelis bombed the Edward Said Public Library and decimated it. In his statement, Abu Toha wrote, ‘All the dreams that I and friends in Gaza and abroad were drawing for our children have been burnt by Israel’s genocidal campaign to erase Gaza and everything that breathes of life and love’.

When we were writing The Joy of Reading, about public libraries in Kerala (India), China, and Mexico, we thought too about similar libraries in Gaza, many of them built and run by volunteers. Israel’s attack on public libraries is no accident: it destroys spaces that rescue collective life, that foster critical thinking, pride of Palestinian heritage, and a consciousness that gives the confidence to dream about the future. As Paloma Saiz Tejero of the Brigade to Read in Freedom told us for that dossier, ‘Books allow us to understand the reason that constitutes our being, our history; they raise our consciousness, expanding it beyond the space and time that ground our past and present… Thanks to books, we learn to believe in the impossible, to distrust the obvious, to demand our rights as citizens, and to fulfil our duties’. The occupation does not want the Palestinian people to believe the impossible; just like it sets out to destroy their homes, hospitals, and lives, it sets out to destroy their ability to dream.

Tings Chak (China), Palestine Will Be Free, 2024. [Courtesy of Utopix and Artists Against Apartheid.]

Abu Toha built the Edward Said Public Library in the aftermath of the fifty-one-day bombardment of Gaza in 2014. During the bombardment, the poet Khaled Juma wrote perhaps one of the most powerful elegies for Palestinian survival:

Oh, rascal children of Gaza.

You who constantly disturbed me with your screams under my window,

You who filled every morning with rush and chaos,

You who broke my vase and stole the lonely flower on my balcony,

Come back —

And scream as you want,

And break all the vases,

Steal all the flowers.

Come back.

Just come back.

Just come back.

Warmly,

Vijay

Monthly Review does not necessarily adhere to all of the views conveyed in articles republished at MR Online. Our goal is to share a variety of left perspectives that we think our readers will find interesting or useful.