CT loses $20M as Trump cuts digital equity programs

Employees at the Hartford Public Library were overjoyed early this year when they learned they’d be receiving $50,000 to help expand digital literacy and skills in the region.

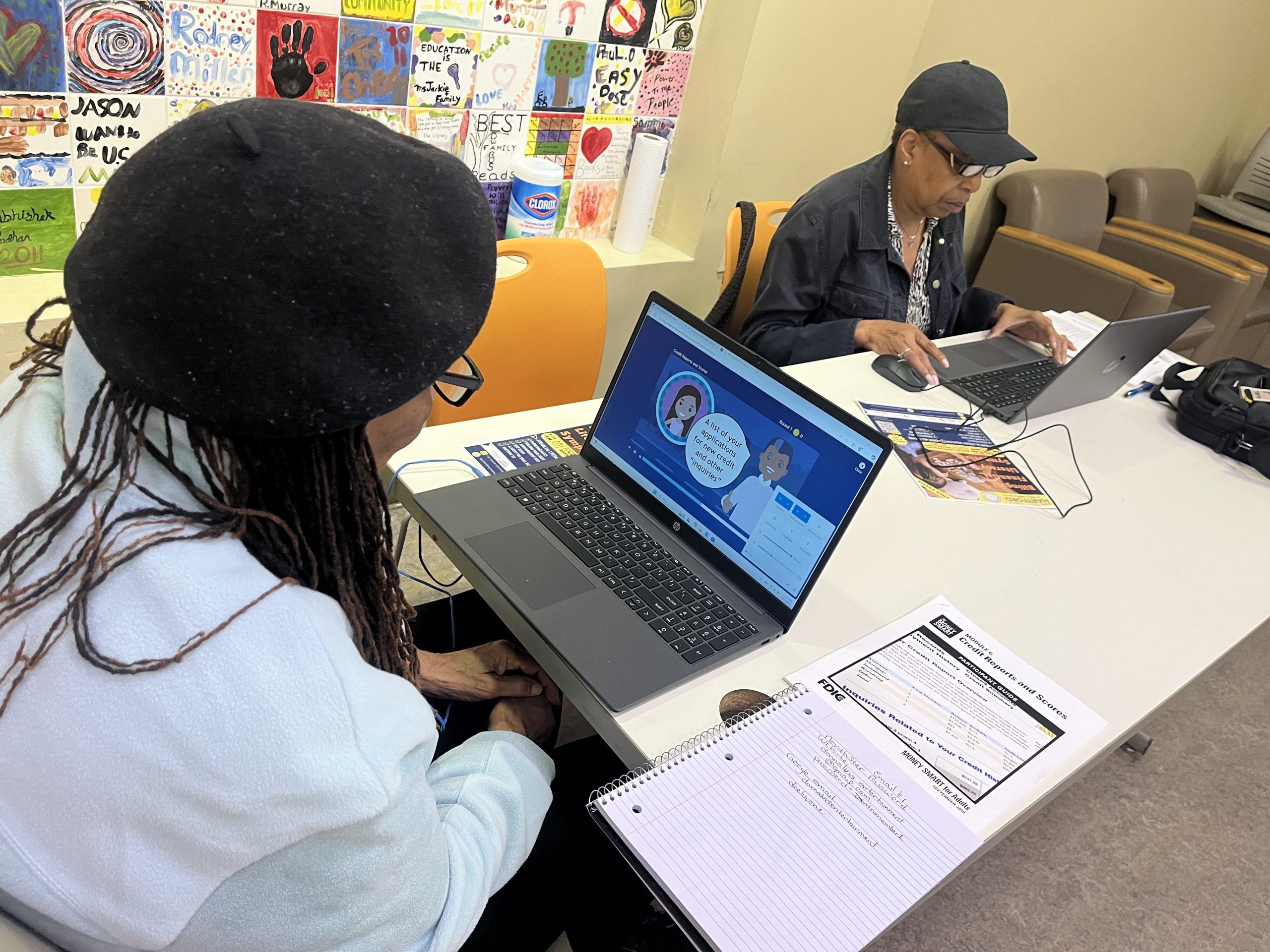

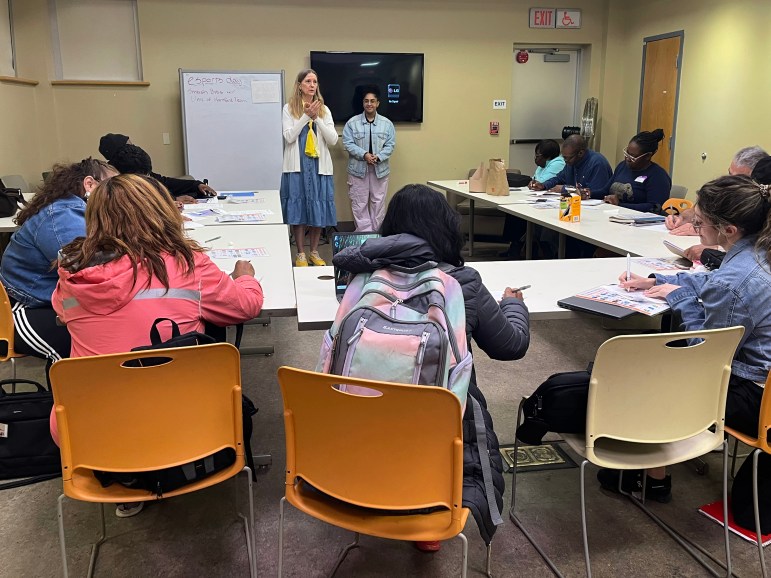

Staffers immediately got to work on a pilot program, using the money to support a “Community Digital Literacy Pilot” to help residents navigate the internet and use devices like smartphones and laptops. This spring, the library system hired a program manager and three part-time digital navigators — who provide technical assistance with the internet — to hold office hours and teach skills classes in English and Spanish. Posters and flyers were finalized, laptops were purchased, and a marketing campaign was expected to launch in late May.

Library leaders knew they were addressing a significant need — one felt not only in cities like Hartford but in communities across Connecticut. According to state research, while roughly 73% of people in Connecticut have access to internet-capable devices, just 64% have the skills needed to use those devices. Advocates hoped programs like the one planned in Hartford would go a long way in closing that gap.

Those hopes were dashed in May when President Donald Trump took to Truth Social to announce he was cutting funding for the Digital Equity Act, a Biden-era federal grant program that supported the Hartford library pilot and other projects in states across the country.

The president called the program “illegal,” adding that it was “racist” for seeking to teach digital skills and improve internet access in minority communities. Other vulnerable populations included in the program — rural populations, veterans and low-income households — went unmentioned.

On May 9, one day later, the administration sent a formal letter to every state, officially terminating the $2.75 billion grant program.

Just like that, the money for the Hartford Public Library program was gone.

“We had our toe in the water,” said Bonnie Solberg, the director of public services for Hartford Public Library. “And then the money got pulled.”

In recent weeks, the federal government has made sweeping changes to Biden-era programs that sought to close persistent inequities in internet access and digital knowledge. The changes have put the futures of several federal broadband initiatives in jeopardy, including efforts to expand internet connectivity and make access more affordable.

The Digital Equity Act was cut completely, pulling a vital funding source out of the biggest effort to improve the digital skills of vulnerable communities in American history.

That loss, state and national advocates told The Connecticut Mirror, will not completely end efforts to close digital divides in the state. But it will force a change in strategy, requiring organizations to find new approaches to the problem just as they were closing in on solutions.

“When you constrain the funding, you constrain the timeline and the impact,” said Doug Casey, executive director of the Connecticut Commission for Educational Technology.

Pulling the plug on $2.75 billion

The Digital Equity Act was passed by Congress in 2021 as part of the larger bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. The bill was a key piece of the Biden administration’s policy agenda, and it arrived as the COVID-19 pandemic was forcing the nation into remote work and online classrooms — throwing into stark relief who had internet access and who did not.

Lawmakers directed billions of dollars in federal investment into closing those divides. The $42.45 billion Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) program was enacted to improve and expand internet connections and access in every state. The smaller $2.75 billion Digital Equity Act, which focused on building the digital literacy skills needed to make the most of those connections, served as a companion.

In Connecticut, where 92% of households have access to the internet, the Digital Equity Act was seen as a big help. “What we found was that regardless of connection, people just didn’t have the skills that they needed to use the technology effectively,” Casey said. “They didn’t feel comfortable online.”

Casey’s office has worked to expand digital access and knowledge in the state for years, and it was the natural choice to lead local digital equity efforts. In early 2024, the commission announced that it had completed a 300-page “digital opportunity” plan outlining the skills gaps in the state, the communities and populations most affected by a lack of digital literacy, and Connecticut’s community-driven proposal to remedy those divides.

The resulting plan, “Connecticut: Everyone Connected,” aimed to take a long-term approach that would tackle a range of interrelated issues. It promoted the creation of pilot programs that would connect state residents directly with teachers and skills classes, and it called for indexing resources and building an asset map to show exactly where those support providers are located in the state. A new digital equity curriculum would make it easier to teach and review standard concepts with residents on a recurring basis.

The policy required states to focus their plans on certain “covered populations” — groups the federal government determined needed special attention: veterans, low-income communities, seniors over the age of 60, people with disabilities, those with low literacy or limited English skills, and racial and ethnic minorities. The largest community was rural populations, defined as anyone who does not live in or near a town with a population of 50,000 or more.

Connecticut’s digital equity plan was approved by the federal government in March 2024, and the state was waiting to receive the funds. In total, Connecticut was set to receive more than $20 million, a mix of state funding and money for local organizations that won a competitive national grant application process.

“This was a fundamental program to get people online and, more than that, to allow people to participate in the modern world,” said Drew Garner, the director of policy engagement for the Benton Institute for Broadband & Society, a national organization supportive of the digital equity money. “Virtually everything we do, from looking up transportation, using the bus, to accessing courts, to using government 311 services, to finding a job, the whole modern world basically has some online component.”

“This was a fundamental program to get people online and, more than that, to allow people to participate in the modern world.”

Drew Garner, the Benton Institute for Broadband & Society

That significance has not protected the program from federal scrutiny. As of now, the digital equity funds have been pulled back from states before they could ever use them.

And the Trump administration has altered the larger BEAD program, removing many of its initiatives that supported climate change resilience, workforce diversity and broadband affordability. States must now update and resubmit their proposed broadband plans within the next few weeks, a rapid turnaround after months of initial planning.

In a statement provided to CT Mirror, a spokesperson for the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, the federal agency tasked with overseeing both the BEAD program and the Digital Equity Act, defended its changes.

“Congress created the BEAD program to expand Americans’ access to high-speed internet. More than three years later, the program hasn’t connected a single person to broadband,” an NTIA representative said in an emailed statement. “The changes we’ve announced will help the BEAD program move forward quickly, and any time spent implementing these reforms will be outweighed by the savings in time and money from the increased competition, reduction in regulatory burdens and streamlined permitting.”

The agency declined to respond to questions about the end of the Digital Equity Act.

An ‘absolutely critical’ lifeline

Digital equity advocates say the loss of the federal funding will be felt all over the state, hampering efforts to help vulnerable communities build the skills needed to succeed in school, in the workforce, and in daily life.

Many of the efforts were already underway.

The United Way of Connecticut was working on changes to its long-active statewide 211 hotline, which is used to connect people in need with resources like housing shelters, mental health providers and utility assistance. The organization had planned to use some of the federal money to expand its database of digital literacy resources and programming. That information would also help the state create an asset map showing the places where additional investment is needed.

With the federal funding now off the table, the organization says it will need to adjust its plans.

“There’s nothing that we can do that would replicate those millions of dollars that would go into creating new services,” said Amy Casavina Hall, senior vice president of strategic partnerships, development and communications at the United Way of Connecticut.

The federal termination will also pull $11.9 million in competitive grant funding from Capital Workforce Partners, a regional workforce development board that was hoping to expand digital access in the state’s north-central region.

“This grant would have provided us with the capacity to serve 5,000 households,” CEO Alex Johnson told reporters at a recent press conference. “It would have given us the capacity to support 18,000 individuals, to give them the skills that they need to be able to maneuver in this society.”

East Hartford resident Elaine Andresen said she knows firsthand the importance of digital equity programs. The retired school teacher has been working with her local library to access the support of a digital navigator to help her use the internet and get connected to online banking.

“It just is nice to have a service,” Andresen said at a recent press conference, noting that Connecticut’s senior citizens often struggle with digital skills as technology continues to change. “You can have the equipment, and people can help you.”

The digital navigator who worked with Andresen, Magdelena Holler, has been teaching digital literacy skills in the area since 2021, helping people who walk into East Hartford’s Wickham Memorial Library. She meets regularly with more than a dozen clients, assisting them with everything from accessing a website to signing up for a new email address.

“There’s an assumption that everybody knows [how to use the internet] or that everybody has access, and that is just not true,” Holler, who also works as East Hartford Public Library’s digital inclusion manager, said. “Not everybody has the devices, and not everybody has the knowledge to use those things safely. It’s absolutely critical for folks to be able to do things like sign their kids up to school, check their own health records, cancel and make appointments.”

With funding gone, CT looks for a way forward

Last week, a group of concerned advocates, local and state officials and community members gathered at the Wickham library, joining U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal in lamenting the loss of the federal money and calling for the Digital Equity Act to be restored.

“We wouldn’t tolerate children being unable to read books — so why tolerate people being denied the tools to read the digital world?” Blumenthal said, adding that he believed the funding cuts were “mean-spirited” and “stupid.”

“This is not just a loss of funding — it’s a betrayal of public trust,” he later added. “These programs are about basic survival, finding jobs, accessing health care, communicating with your children’s schools. Rescinding this grant is cruel and senseless.”

It is unclear exactly what will happen next, but without the federal funds, it will be up to state and local governments to find a replacement. It is possible some states may consider suing the federal government to restore the digital equity funds. The Connecticut attorney general’s office did not respond to a request for comment on whether it was considering legal action.

The state’s broadband office, meanwhile, said in an email that it is working to ensure that Connecticut’s larger BEAD reapplication will comply with the federal government’s new guidance.

Without the Digital Equity Act, advocates worry that any reformed broadband plans will come up short in helping the communities that need the internet the most.

“People are still getting scammed every day. People are still not able to apply for jobs, people are still not able to talk to their doctors. All of those things are still happening.”

Angela Siefer, National Digital Inclusion Alliance

“The fact that we still need [equity] programs hasn’t changed,” said Angela Siefer, the executive director of the National Digital Inclusion Alliance, which is leading a coalition calling for the Digital Equity Act to be restored. “People are still getting scammed every day. People are still not able to apply for jobs, people are still not able to talk to their doctors. All of those things are still happening.”

“What’s changed is that we don’t have this federal investment that would allow us to figure out what works,” she added.

In Hartford, Solberg is still figuring out how the library system will move forward. With digital equity funding gone, she had to terminate the contracts for the digital navigators and their manager, a situation that she called “painful.” More than a dozen purchased laptops, intended to help residents in the community build skills, currently sit in her office.

Solberg said it’s a depressing situation, but the library system will figure out a different way to provide support to the community.

“The need is real, and [we] want to be part of meeting the need,” she said. “This door is closed, but we’re already thinking about other doors or a window we can climb through.”