A large language model digital patient system enhances ophthalmology history taking skills

Ophthalmic dataset construction, LLM selection, and model fine-tuning

First, we curated a comprehensive ophthalmic dataset by incorporating data from various sources, including EHRs, clinical guidelines, ophthalmology textbooks, multiple-choice questions, and patient-doctor consultation dialogs (Fig. 2a, b). The dataset was processed into an instruction-output format, with the accuracy of the data being validated by ophthalmologists. The final dataset comprised 59,343 entries, covering a wide range of ocular diseases (Fig. 2c).

Using previously established method28, we designed multiturn prompt templates and constructed a dataset with an instruction-output format to process the online medical consultation dialog data, by using historical dialog and patient notes as context and the patient’s actual response as the output target. For nondialogue text data such as EHRs, clinical guidelines, and medical textbooks, we utilized text headings as weak supervision signals and designed rule-based templates to automatically map the text into the dataset using LLMs. The detailed processes are provided in Supplementary Note 2.

To accurately reflect real-world performance and nuanced differences of these models, the performance of several LLMs were evaluated by human doctors using previously established evaluation standards28. Briefly, to enable human evaluation of the LLMs, we adopted an approach similar to the model comparison method used in the Chatbot Arena project where human evaluate the output of LLMs61. We prepared 50 Chinese instruction tasks to evaluate the accuracy of LLMs in terms of ophthalmic knowledge, information extraction capabilities, and Chinese instruction alignment abilities (Fig. 2d). Considering the models’ capabilities and usability, we included Baichuan-13B-Chat, LLaMA2-Chinese-Alpaca2 (13B), LLaMA2-70B-Chat, ChatGLM2-6B and GPT-3.5 Turbo (ChatGPT); detailed model information is provided in the Supplementary Note 3. Apart from GPT-3.5 Turbo, among the five models evaluated, Baichuan-13B-Chat demonstrated the best overall performance in understanding and responding to Chinese instructions and was therefore chosen for our study (Fig. 2e).

To enhance the model’s ability to perform effectively in our specific context, we fine-tuned it using 8 Nvidia Tesla A800 GPUs (each with 80GB of memory). Fine-tuning helps adapt a pre-trained model to a specialized task by updating its parameters based on new data. To make this process more efficient, we used LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation)62, a technique that reduces the number of trainable parameters by introducing low-rank matrices, thereby lowering computational requirements. This was implemented within DeepSpeed63, an advanced deep learning framework designed to optimize large-scale model training. The key training settings were as follows: Batch size: 4 (number of samples processed at a time), Learning rate: 5e-5 (determines how much the model updates during training), Weight decay: 0 (no additional penalty for large weight values), Scheduler: Cosine (gradually adjusts the learning rate over time), and Training epochs: 25 (one epoch means the model has seen the entire dataset once). The training process lasted approximately 19 h. The best results were observed at epoch 20, where the model demonstrated superior performance on automated evaluation metrics (BLEU and ROUGE, Fig. 2f) and was preferred in human assessments (Fig. 2g). Based on these findings, we selected this version for further studies.

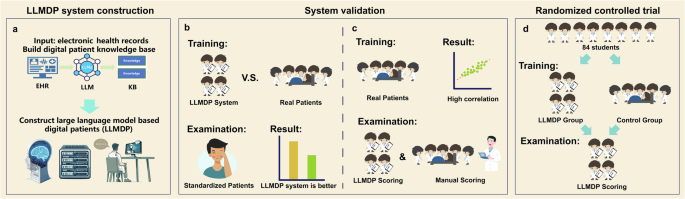

The development of the LLMDP system

In developing the LLMDP system, we utilized the fine-tuned LLM to analyze patient notes and generate a Knowledge Base (KB) for simulating digital patients (Fig. 3). First, in accordance with the syllabus requirements, 24 ocular diseases, all of which are prioritized for student mastery, were included (Supplementary Note 1). Next, a clinical inquiry question set for these 24 ocular diseases was compiled by enumerating all the questions concerning symptoms, signs, and pertinent notes based on ophthalmology textbooks, standardized patient notes, and outline and scoring criteria of previous standardized history-taking exams. EHRs, including patient notes and slit-lamp photographs as the ocular images, for patients with the 24 diseases were gathered. Using the fine-tuned LLM, all questions in the clinical inquiry question set corresponding to each disease were answered based on the patient notes, and the patient information sheet was generated using a standard prompt template (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Importance weights were assigned to each question in the patient information sheet based on the diagnostic significance of each question after the expert panel discussion64 (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7), with specific scores calculated according to a predefined rubric: 5 points for patient identification and demographics, 50 points for history of present illness, 25 points for past medical history, and 20 points for other medical history. The sheet was then combined with the slit-lamp photographs to form a KB for the DPs.

When participants interacted with the LLMDP system, their inquiry audio was converted into text through an automatic speech recognition (ASR) algorithm65. Then, the system matched the inquiry questions with the KB of the DPs using Sentence Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (SBERT) embeddings (distiluse-base-multilingual-cased-v1)66 as a semantic textual similarity model. If a match was found, then the corresponding answer was output. If no match was found, then the LLMDP generated an answer based on the entire patient note using a prompt template (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Notably, the LLMDP system is designed to understand the meaning and intent behind students’ questions rather than requiring fixed wording patterns. Next, the answer generated in the previous phase was refined into more colloquial language using the LLM, simulating the patient’s tone to enhance realism; at the same time, the LLM could randomly assign personality traits to the patient, further enriching the authenticity of the dialog scenario (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Finally, the response was converted into speech through the text-to-speech (TTS) algorithm67 and provided as feedback to the students via the human-computer interaction (HCI) interface (Fig. 3b).

The development of the automatic scoring system

To establish a scoring system to evaluate the participants’ proficiency in medical history taking, we first identified key points in clinical consultation for each patient based on the objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) checklists for ophthalmic history taking68,69, which are widely used as the National Medical Licensing Examination70 along with ophthalmologic textbooks and standardized medical records (Supplementary Fig. 3). Then, we preliminarily formulated medical inquiry questions about each key point and recruited experts in the relevant subspecialties for group discussion to determine the final medical inquiry questions and evaluate their clinical importance for each case. The expert panel consisted of 9 professors, including 3 cataract specialists, 2 glaucoma specialists, 1 retina specialist, 1 cornea specialist, 1 orbit specialist, and 1 trauma specialist. The specific discussion process64 is outlined in Supplementary Fig. 3: first, the importance of each category of medical history was determined (Supplementary Table 6), followed by assigning scores to each individual question, with an illustrative example shown in Supplementary Table 7.

Upon the completion of history taking, the dialog between participants and the DP was used to calculate the medical history taking assessment (MHTA) scores. During the history taking practice phase, after each session, the system displayed real-time scores, including points earned and points lost, to facilitate improvement in the examination phase, this feedback feature was turned off.

User instructions for the LLMDP system

The LLMDP system interface includes a voice chat window where users verbally interact with the system, an avatar with an image of the real patient’s eye represents the DP’s visual presence and a feedback window showing user progress (Fig. 3c, d). After entering their student ID and choosing a topic, users are directed to the conversational interface designed for practicing medical history taking. This interface comprises three main components. First, a dynamic virtual character is presented on the main screen, enhancing the realism of the interactions, and simulating real-life patient conversations. Second, the response section appears beneath the virtual character. Here, students can engage in continuous dialog by either using the “speak” button for voice commands or typing their responses directly. Upon submitting their responses, the system provides immediate feedback through both text and voice outputs. Finally, the sidebar features question indicators that track the student’s progress. As students address each question in a section, the corresponding checkboxes are marked, offering instant feedback on students’ progress. During the practice period, the system displays feedback in real time which medical history sections the participants had completed. While in the examination period, this feedback feature was turned off. During the training phase, our digital patient simulation deliberately presents scenarios reflecting realistic emotional responses (e.g., a patient experiencing an acute angle-closure glaucoma attack feeling anxious). The system assesses students’ responses, scores their empathetic communication skills, and provides targeted feedback (Supplementary Note 4). Users can access the LLMDP system via smartphones, tablets, or computer browsers. The user guide for the LLMDP system can be found in Supplementary Note 5.

System validation

At the end of development of the LLMDP system, we conducted two initial experiments to preliminarily validate its effectiveness in medical history-taking training and assess the correlation of its automated scoring function with manual scoring.

Validation experiment 1: Effectiveness in medical history taking training

This experiment involved 50 fourth-year medical students from the Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University. The goal was to explore the potential of the LLMDP system to enhance medical history taking skills compared to traditional methods. Participants were divided into traditional real patient based training group and LLMDP-based training group (Fig. 4a). Traditional real patient based training refers to the conventional teaching method where students, in groups of five, engage in medical history taking practice under the guidance of a physician instructor, while interacting with actual patients in a clinical environment. Under traditional training, participants were trained with three real patients for 1 h, with 10 min of training and 10 min of explanation for each case. In contrast, “LLMDP-based training” refers to each student independently utilizing the LLMDP system for individual practice. Under the LLMDP system, three cases were provided, and the training duration was 1 h. During the examination, all participants conducted medical history-taking assessments with SPs. Their performance was evaluated by attending doctors following the OSCE criteria and was compared between two groups with t test.

Validation experiment 2: Correlation of automated scoring with manual scoring

This experiment involved a different cohort of 50 fourth-year students who were undergoing traditional clinical internships at the same institution. The goal was to assess the correlation of the LLMDP system’s automated scoring compared to manual scoring by attending doctors. Participants were consecutively evaluated twice using both assessment methods: first by real patient assessment (manual scoring), followed immediately by an assessment using the LLMDP system (LLMDP system scoring), without receiving any feedback between the two assessments (Fig. 5a). To minimize recall bias and ensure a fair comparison, different cases were used for the real patient and LLMDP assessments. In the real patient assessment, students conducted medical history taking assessment with actual patients in a clinical environment, and their performance was evaluated by attending doctors following the OSCE criteria. Pearson’s correlation coefficient and scatter plot were used to determine the correlation between the scores obtained from the LLMDP system and those from real patient encounters.

Design and procedures of the randomized controlled trial

The predefined protocol of this trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center (identifier: 2023KYPJ283) and was prospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Registration Number: NCT06229379). The inclusion criterion for this study was fourth-year students majoring in clinical medicine at the Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University. Having recently completed their theoretical courses and exams in ophthalmology, these students were about to embark on the clinical rotation stage. Prior to this phase, they had not received any clinical training. After online and offline enrollment, a total of 84 students ultimately participated in this study and signed informed consent forms.

In the trial from Nov. 14 to Dec. 7, 2023, 84 participants were divided into two groups, with 42 individuals assigned to the control group who underwent traditional real patient based training and another 42 participants assigned to the LLMDP group where they underwent LLMDP-based training (Fig. 6a). Traditional real patient based training refers to the conventional teaching method where students, in groups of five, engage in medical history taking practice under the guidance of a physician instructor, while interacting with actual patients in a clinical environment. Following standard clinical teaching practices, participants in the traditional training group engaged with three real patients over the course of 1 h, with each case allocated 10 min for history taking training and 10 min for instructor feedback. The LLMDP system mirrored this structure, providing three cases within the same training duration as the control group. Additionally, before taking exams with the LLMDP system, each student was provided with a 10-min orientation to ensure their familiarity with the LLMDP exam system.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the participants’ MHTA scores. The scores for MHTA were automatically calculated by the system based on the dialogs, according to predetermined scoring criteria (Supplementary Table 5). Additionally, we analyzed the impact of LLMDP training on specific history taking components by deconstructing MHTA into key subitems, including identification and demographic information, history of present illness, past medical history, and other medical history.

The secondary outcome is to investigate the attitudes toward the application of LLMs in medical education, as well as the differences in empathy toward patients between the two groups. All participants completed a standardized quantitative questionnaire based on the widely used five-point Likert scale about their attitudes toward the application of LLMs in medical education after using the LLMDP system after the trial (Supplementary Note 6). Additionally, at the end of the trial, all 84 students and their 8 supervising teachers were asked to independently discuss questions about the use of LLMDP in medical education. The results of the students’ discussion were recorded, transcribed and coded by three different authors (MJL, SWB, LXL). A panel of 9 experts participated in the discussion to provide further insights. Following discussions in regular meetings, a category system consisting of main and subcategories (according to Mayring’s qualitative content analysis) was agreed upon71. Text passages shown in Supplementary Table 2 were used as quotations to illustrate each category. Inductive category formation was performed to reduce the content of the material to its essentials (bottom-up process). In the first step, the goal of the analysis and the theoretical background were determined. From this, questions about LLMDP in medical education were developed and presented to the students for discussion. Two main topics were identified, namely positive and negative attitudes toward LLMDP in medical education. In the second step, we worked through the individual statements of the students systematically and derived various categories: accessibility, interaction, and effectiveness. To avoid disrupting the MHTA process, we recorded the entire session in the system’s backend, and after the assessment, an expert panel used the recordings to assess students’ empathy performance, according to the scoring criteria shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a.

Randomization and blinding

The participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either the traditional teaching group or the LLMDP teaching group. Stratified block randomization was utilized, with theoretical ophthalmology exam scores serving as the stratification factor. The randomization process was carried out by a central randomization system.

The collection, entry, and monitoring of primary and secondary outcome data were performed by staff who were blinded to group assignment. Participants were not blinded due to the nature of the interventions. Statistical analyses were performed by an independent statistician blinded to group allocation.

Statistical analysis

The trial sample size calculation was based on the primary outcome (MHTA). In the pilot study, the control group (n = 10) had a mean score of 54.59 ± 7.33, while the experimental group (n = 10) had a mean score of 62.05 ± 9.13. Based on these findings, we assumed a seven-point improvement and an SD of 9.5, where the effect size was estimated to be 0.74, yielding a sample size of 40 participants per group, 80 in total. The pilot data were not included in the final analysis. Ultimately, 84 participants were enrolled in the formal trial to account for potential exclusions. The sample size was calculated using PASS 16 software (NCSS, LLC, USA).

The intention to treat population is same with the population of per protocol in this trial since no students discontinued or withdrew after recruitment. Descriptive statistics, including the means and SDs for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, were employed to present the data. The baseline characteristics of the participants in the treatment groups were compared using t tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. Continuous data were examined for normality using Shapiro–Wilk test. Independent t tests were conducted to assess differences in MHTA scores between study groups. To address multiplicity issues, all p values and confidence intervals for the subitem scores of the MHTA were corrected using the Benjamini‒Hochberg procedure to control the false discovery rate (FDR) at 0.0572.

All the statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS statistical software for Windows (version 24.0, IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA), GraphPad Prism (version 9, GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA), and R (version 4.3.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).