A systematic review of influences on engagement with remote health interventions targeting weight management for individuals living with excess weight

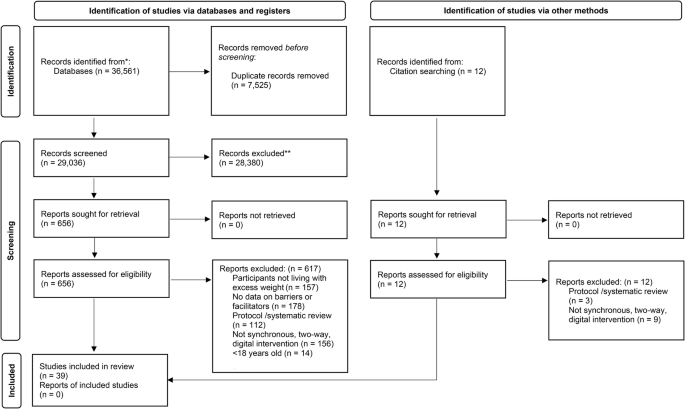

The search identified 36,561 titles and abstracts. After removing duplicates, the remaining 29,036 titles and abstracts were screened for potential inclusion. Following initial screening there were 656 full-texts reviewed, which identified a total of 39 studies [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80] which met the inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

Fifteen of the included studies (41%) were randomised controlled trials [44, 50, 56, 57, 59, 61,62,63,64,65,66,67, 74, 77, 80] with the other quantitative designs including non-randomised experimental [60, 69], pre-post [67, 75, 78, 79], cohort, cross-sectional [42, 43, 71] and feasibility/pilot studies [45, 47, 49, 52,53,54, 58]. Seven studies (19%) utilised only qualitative designs, including focus groups [70, 72], interviews [51, 55, 76], and a mixture of both [46, 48]. Seventy per cent (n = 27) of all studies were conducted in the United States [43,44,45, 47,48,49,50, 54, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64, 66, 67, 71,72,73, 75, 77,78,79,80] with the remaining undertaken in England [42, 65, 76], Australia [67, 70], Norway [46, 55], Scotland [52, 74], Wales [51], Finland [69] and Switzerland [53]. Within the studies, the intervention sample sizes ranged from 10 to 2818. The mean age ranged from 31.5 to 72.9 years. Intervention studies mostly included participants with a mean age between 40 and 49 years (n = 14) [42, 44, 56, 59, 62,63,64, 68, 69, 73,74,75, 77, 80] and 50 and 64 years (n = 12) [45, 50, 54, 57, 58, 60, 61, 65,66,67, 78] with a few studies targeting younger (mean age 20–40 years) [79] and older (mean age of >65 years) cohorts [47, 49, 52].

Participants’ ethnicity varied across studies; however, it is important to note that ethnicity was not reported for eleven (30%) of the articles included [46, 48, 52, 55,56,57, 63, 69, 70, 76]. Of the studies that did report ethnicity, only eight were identified as having an ethnically diverse sample, defined as 50% or more of the whole sample as being from an ethnic minority group [43, 50, 51, 58, 64, 68, 72, 77]. Most studies included all adults regardless of sex; however, several studies specifically targeted females [45, 67, 71, 79, 80] and males [65]. Ten studies reported employment status, with five of these revealing the sample had an employment rate of less than 70% [50, 51, 55, 67, 78]. Twenty-four studies reported educational attainment, with two studies having a sample where less than 20% had a college degree [50, 59].

The ‘remote’ intervention modes of delivery varied across all of the studies which included the use of individual/group-based telephone calls [50, 54, 57, 58, 60, 61, 67, 68, 73, 78], video-conference calls [42, 47,48,49, 51, 56, 59, 62, 63, 66, 69, 70, 80], interactive websites [52, 53, 63, 71, 72, 74,75,76, 81], mHealth smartphone applications [43, 44, 50, 66, 74, 77], social networking sites [45, 79], emails [62, 63, 65], online chat messaging/web-forums [55, 62,63,64,65] and personalised/interactive text messaging [61, 67, 68, 70, 77, 80]. Many studies delivered the intervention through a combination of modes such as telephone calls alongside personalised text messaging [61, 67, 68, 70]. Some studies delivered the intervention through mHealth smartphone applications with the addition of telephone calls [50], video-conference calls [66], text messaging [77] or interactive websites [74]. Sixteen (43%) studies incorporated a remote monitoring component as part of the intervention [44, 45, 47,48,49, 52, 54, 56, 59, 60, 66, 72, 74, 75, 77, 80], including wearable technology to self-monitor physical activity [44, 45, 47, 49, 50, 52, 59, 72, 75, 77] alongside platforms to record and self-monitor diet, weight [44, 54, 56, 66, 72, 75, 77] and ‘lifestyle’ behaviours [59]. Several studies included telehealth remote monitoring [48, 60] or WIFI-enabled smart scales [50, 61, 77, 80] which exchanged data synchronously to a third party for monitoring. All intervention and population characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Engagement with a remote weight management intervention

Patterns related to the engagement with remote digital weight loss interventions, classified as the target behaviour for this study, were examined. This focused on the uptake (recruitment to the study/intervention), the duration of usage (retention/adherence) and interaction (automated recorded data including logins and data entry, attendance) with the intervention.

Several studies required participants to be eligible to have access to a high-speed internet connection [47, 59, 62,63,64, 72, 75, 76, 81, 82] and/or required them to have access to the technology that the intervention was being delivered through, which in the majority of cases was through smartphones [44, 50, 74, 77, 79] and/or laptop/computers (which in some instances required specific operating system requirements) [50, 62,63,64].

Most studies that reported a recruitment rate (n invited/n consent) achieved a consent rate of 40% and above. The consent rate was 80% for one study [59]; followed by six studies at 60–79% [42, 44, 45, 47, 52, 59] and seven studies at 40–59% [49, 54, 61, 64, 74, 78, 80]. One study, which was based on delivering weight management sessions via video conference, revealed that older participants and/or those from an ethnic minority group were significantly less likely to consent compared to white younger participants [42]. The most common reason for lack of consent was a lack of interest [45, 47, 49, 64, 73] or perceived need [67] to participate in a remote weight management programme. Inconvenience, alongside competing responsibilities [44, 47, 49], preference for face-to-face support [42, 51, 54], lack of digital skills or technology capability [42, 61], lack of access to the internet [42] or technology, [67] refusing to use their smartphone for the intervention [67] and anxiety about technology [49] were also shown to be barriers to consent. Four studies revealed a consent rate below 40% (0–19% [51, 65, 79], 20–39% [73]). The low levels of consent in these studies, where specified, mostly related to decline (no reason specified) and/or non-response [65, 79]. In one study, 37% declined as they opted for a dietitian-led weight management group through face-to-face sessions rather than synchronously using videoconference [51].

The majority of studies achieved high retention (n enrolled/n completed), with fourteen studies achieving a retention rate of 90% or above [45, 50, 52, 54, 59,60,61, 64, 68, 69, 75, 77,78,79] and four which achieved full retention (100%) [45, 54, 61, 77]. These studies all had interactive components; for example, two were delivered via telephone consultations with the ability to log and track behaviour [54, 61], one study was delivered in hybrid (face-to-face/online) format through a social network website [45], and the other involved a mHealth App alongside personalised text messaging [77]. The inclusion criteria on some studies required participants to have the ability and skills to use the technology, such as sharing data [59] and/or have the willingness to use the technology required as part of the study [68] or already using the platform the intervention was being delivered through (i.e., social networking site) [79]. Where studies used a pre-requisite to either have familiarity or current use of the technology the intervention was being delivered by, there was a trend towards higher retention, with all studies achieving a retention rate of >90%.

Only one study had a retention rate below the 70% threshold [44] (63%). This study had a predominantly ‘middle-aged’ (M = 44.9; SD = 11.1) female (78%) sample with high levels of ethnic diversity (49% African-American). The delivered intervention included intensive biweekly diet and exercise counselling sessions delivered by a nutritionist coach (months 2–6) alongside a weight loss mHealth app, which provided real-time feedback, self-monitored food intake and activity, and tracked progress with weekly weigh-ins encouraged with opportunities for social networking and support. Tracking data identified that intervention usage was highest in the intensive counselling plus smartphone group, with 70% of all sessions attended compared to intensive counselling only (58%).

Behavioural diagnosis: COM-B analysis of influences on engagement with remote weight management technologies

The findings revealed a wide range of influences on engagement with remote weight management interventions. When mapped to the COM-B model [32], all constructs in the system were identified via themes related to: psychological capability (n = 9); physical capability (n = 3); reflective motivation (n = 19); automatic motivation (n = 11); physical opportunity (n = 8); and social opportunity (n = 11). The schematic framework is depicted in Table 3. This is explained in more detail below.

Physical capability (TDF domain; skills)

Physical and/or functional limitations [71] were presented as a barrier which would impact on engagement with a digital intervention in a cross-sectional survey with women who had completed cancer treatment. Findings from a qualitative study with older adults (aged ≥65 years) identified that sensory limitations (e.g., hearing, vision) [48] would impact their ability to engage with a remote intervention.

Psychological capability (TDF domains: knowledge; cognitive and interpersonal skills; memory, attention and decision processes; behavioural regulation)

The knowledge that comes from familiarity and prior experience [43, 44, 50, 51, 61, 71, 74] alongside having the digital competency and technical skills to use the technology [42, 45, 48, 60, 66] were revealed to be important factors that influenced engagement with a remote intervention. Having the acquired knowledge and skills on how to perform a health behaviour [51, 59, 71] and the knowledge and skills on how to set goals and regulate behaviour [74, 78] were also identified as important. Facilitators also included self-monitoring and tracking behaviour [44, 46, 52, 59, 65, 71, 72, 76], shaping knowledge [46] and receiving biological [46] and tailored feedback [46, 59, 67, 70, 73]. Conversely, cognitive limitations (memory loss and forgetfulness) [48, 74], particularly among older populations, negatively impacted how some participants engaged with a remote intervention. Literacy ability (reading and writing) or lack of was shown to influence the use of a remote intervention, reported in one study [55]. In this study, the majority of the sample were only educated to high school level (61%) with around one-third identified as being unemployed.

Reflective motivation (TDF domains: beliefs about capabilities; beliefs about consequences; optimism; social/professional role and identity; intentions; goals)

As with traditionally delivered interventions, the desire and motivation to lose weight [43, 44, 53, 71] alongside the perceived confidence in the capability to change and adapt health behaviour [46, 51, 71, 74, 78] were all found to be important facilitators that influenced engagement of a digital intervention. Some participants declined an intervention as they had a preference for a face-to-face mode of delivery [42, 51] rather than using a remote method. This was particularly noted in studies that included weight management programmes which have been traditionally delivered in person, and/or they were given the option to attend in person. Perceptions related to the ease of use and simplicity [44, 48, 49, 60, 65, 66, 70, 72, 74, 76], perceived usefulness of technology and/or intervention [47,48,49, 58, 60, 72], perceived capability to use technology [61, 62] and the willingness to learn or adopt the technology [44, 74] were all shown to be important facilitators to engage with a remotely delivered weight loss intervention. Perceived confidence to interact with others using technology [61, 67, 71, 74] was also highlighted as being important. This was particularly noted in interventional studies which used group-based interactive elements (video-conferencing, online forums).

Autonomy to choose the platform and technology that the intervention was delivered on [72] and role and identity [46] were also viewed as a facilitator alongside setting goals and planning [46, 59], having motivational discussions [46, 59, 68], and increased autonomy and personal responsibility [51]. In contrast, several studies revealed that the perceived time burden to engage in the intervention [45, 59, 65, 71, 78] was a barrier to continued engagement; however, this mostly related to interventional studies which requested participants to use daily wearable technology alongside frequent self-monitoring of behaviour. Perceptions related to concerns surrounding the privacy of the technology [55, 57, 71], unrealistic expectations [53] and perceived performance or effort expectancy [72] that was involved in taking part in the intervention were shown to negatively impact engagement.

Automatic motivation (TDF domains: reinforcement; emotions)

Emotional factors, particularly anxiety were revealed as a barrier to engagement in remote interventions. This related to embarrassment or anxiety of self-disclosure, [45, 48, 55] alongside anxiety using technology [49]. In contrast, some participants found remote interventions a reduced threat (less stressful and daunting) when compared to face-to-face interactions [51]. One study required participants to approach others to be their ‘peer’ helper which some participants revealed they felt uncomfortable doing [74]. With facilitators, praise (social reward) [46], rewards (material incentives) [46, 53], and natural consequences [46] were all shown to positively reinforce and influence engagement. User dissatisfaction with technology/intervention [60, 66], fear of failure [53] and isolation following the end of the intervention [68] were all shown to be barriers.

Physical opportunity (TDF domains: environmental context and resources)

The convenience of engaging in the intervention remotely, with less need to travel and less impact on competing demands (e.g. childcare, work) [45, 48, 51, 52, 56,57,58,59, 62, 65, 67, 70, 71, 76, 78, 79] alongside reduced cost compared with face-to-face [51, 56, 57] were viewed as the most common facilitators that influenced participants desire to engage with a remote weight-based intervention. Having good levels of functionality and usability of equipment [49, 60, 65, 72, 74, 76, 79], including the opportunity to track, monitor and share behaviour [44, 71, 74, 76] were important facilitators. Technical issues (malfunctions, unresponsive, errors, incompatibility) were revealed to be important barriers that influenced continued engagement in some of the interventions [51, 59, 60, 66, 68, 69, 74]. Many of the interventions required accessing or using specific technology devices or platforms which required particular specifications [48, 49, 51, 52, 56, 60, 65, 67, 72, 76], alongside a high-speed internet connection [43, 48, 51, 61, 65, 66]. Therefore, providing access to these was shown to be integral to consenting to take part in the intervention.

Social opportunity (TDF domain: social influences)

General social support and engagement was identified as one of the most common facilitators [45, 46, 48, 51,52,53, 55, 57, 59, 61, 70, 71, 73,74,75,76, 78], including peer [45, 47, 51, 62, 69, 74] and group support and encouragement [51, 63, 74, 77, 80]. Several studies reported that positive social comparison with peers/others was also viewed as a facilitator for remote interventions [51, 71]. A common facilitator identified among nine studies to engaging with remote interventions was increased accountability [44, 48, 57, 59, 60, 62, 67, 70, 72].

Encouragement and support by a professional or specialist (weight loss/exercise) [43, 44, 46, 49, 53,54,55, 65, 68, 74, 78, 80] was found to be particularly important. However, a survey conducted with primary care patients living with obesity from an ethnically diverse background viewed encouragement and support with healthcare providers [43] less favourably. Maintaining a positive relationship with the professional [54, 65, 72, 80] alongside the provision of non-judgemental care [70, 72] and emotional support [67, 73] were viewed as important. Hybrid interventions, i.e., those that were delivered remotely but had some face-to-face contact, were also viewed more favourably [42, 43, 47, 54, 60,61,62, 64, 65, 67], alongside interventions with regular check-ins [44, 53, 54, 58, 60, 65, 67, 72, 74, 78] and follow up support when the intervention has ended were also viewed important [68, 74, 78].