Applying the principle of justice in digital health

Translating these ethical foundations into practice requires a structured lens through which to evaluate digital health challenges. Drawing on the principle of justice, we propose an adapted framework to assess digital health interventions not only in terms of access and usability, but also in how they address systemic disparities and promote inclusive innovation.

Justice in healthcare is the expression of the idea of equal opportunities and the application of the difference principle when resources are scarce. A process of digital transformation that understands and recognizes the limitations of a large part of the population would not endanger the principle of justice. The speed of this transformation of the system towards digitization has a huge impact not only on users of healthcare services but on healthcare practitioners as well.

Given that health policies are habitually based on distributive justice, we believe it is important to apply this approach in the field of digital health. When we talk about bioethics and digital health, the principle of justice should lead us to uphold the principle of equal opportunities in the distribution of the benefits and burdens that technological advances bring to society. But to properly address justice, it is not enough to follow the equality principle, ensuring full access for everyone to digital health-related devices, procedures, and systems. In the digital transformation, some inequality is inevitable in favor of those who can adapt more quickly to constant change (and this rapid adaptation may even favor the transformation and its benefits). But the principle of justice must follow as well the difference principle, which requires us to guarantee that these changes also, and especially, benefit “the most disadvantaged,” that is, the people for whom this process of adaptation represents a real challenge.

It is one thing to make digital devices available to the population, and another to ensure that they reap the benefits of the digital transformation. It is important to focus on the obstacles posed by an increasingly technological environment that places certain users at a significant disadvantage, and to try to redress a situation that we would be right to consider an injustice.

In this context, then, justice is the provision of equal, equitable, and appropriate treatment. Anyone who has a valid requirement is entitled to receive this treatment. In contrast, an injustice is a wrongful act or an omission that denies people the benefits to which they have a right, or that fails to distribute the burdens fairly.

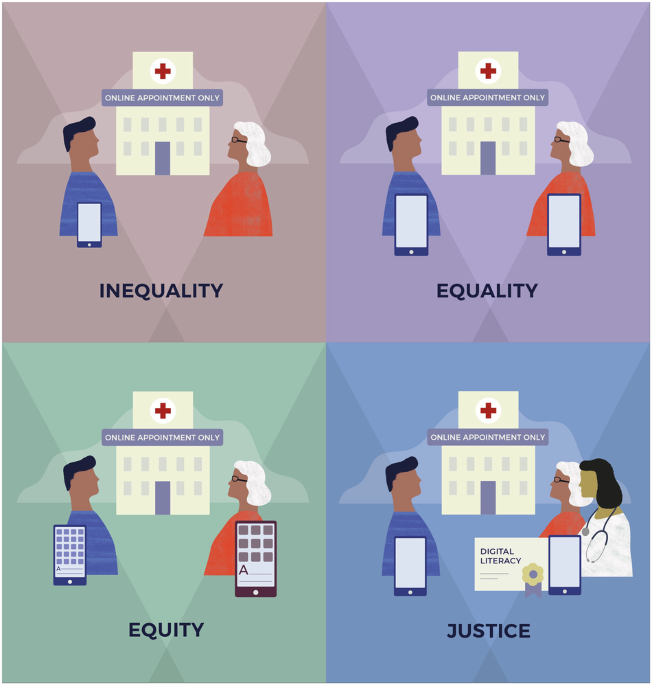

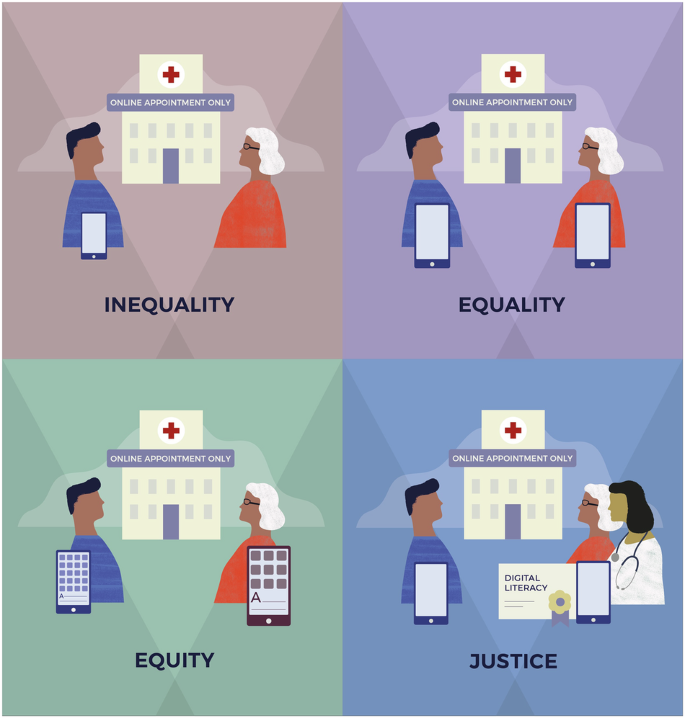

We decided to adapt Tony Ruth’s image23 of equity in digital health and the different concepts linked to the principle of justice in order to highlight the challenges we must address if we genuinely intend to reduce the digital gap (Fig. 1).

Illustrative model adapted from public health equity frameworks, applied to digital access and inclusion. The figure contrasts different levels of resource distribution and structural response: inequality (no access), equality (same access regardless of need), equity (access adapted to individual needs), and justice (removal of structural barriers and active facilitation of inclusion).

According to this adapted image, and drawing on the philosophical concepts of justice, equality, and equity introduced earlier, we illustrate how these principles can be interpreted in the field of digital health:

Inequality: This refers to situations in which one person has access to an internet connection and an active device, while another does not. In the context of digital health, such inequality is particularly relevant in systems that increasingly promote virtual appointments and provide many services through mobile applications and digital platforms. Without adequate support, this shift may exclude large segments of the population who lack digital access or skills, thereby undermining equitable access to healthcare.

Equality: In this scenario, two individuals are provided with the same digital device and internet connection. While this appears to represent equal treatment, it fails to account for specific needs. For example, a person with limited digital literacy or a visual impairment may not be able to use the device effectively, while someone with greater technological competence might find the same resources insufficient. This illustrates how formal equality alone can reproduce or exacerbate disparities.

Equity: Equity involves recognizing differences in individuals’ capabilities and contexts, and taking proactive steps to ensure meaningful access. In digital health, this could mean providing a larger device with enhanced visibility for a user with low vision, or customized support for someone with limited technological familiarity. Equity requires tailoring resources to actual needs, rather than assuming a one-size-fits-all solution.

Justice: Justice goes beyond individual accommodations and involves structural action to eliminate the root causes of inequality and digital exclusion. This includes investing in digital literacy programs for vulnerable populations and appointing digital health facilitators to assist patients in navigating digital tools and accessing the full range of services available. Such measures aim to create a more just and inclusive digital health ecosystem where everyone can participate and benefit.

We believe that this new image responds to a new vision of justice and digital health. In an article published in 202424, we talked about the significant socioeconomic difference between people who have access to new technologies and the skills needed to use them and those people who do not (the digital gap).

However, the digital gap extends far beyond binary access disparities, functioning as a multilayered determinant of health outcomes shaped by intersecting structural, cultural, and technical forces. Contemporary research conceptualizes this divide through the lens of DDH25, which operates across individual, interpersonal, community, and societal levels26.

These complexities are formalized in frameworks like the Digital Healthcare Equity Framework, which integrates equity assessments across five lifecycle phases such as planning, development, acquisition, implementation, monitoring27. Its core innovation lies in binding technical design (e.g., algorithmic audits for bias), community co-creation (e.g., participatory prototyping with marginalized users), and systemic enablers (e.g., policy mandates for interoperability). From an ethical standpoint, failing to recognize these layered determinants risks reinforcing structural injustice under the guise of digital innovation. Furthermore, digital exclusion is often compounded by mistrust in institutions, especially among communities historically marginalized or subject to surveillance, making trust-building a critical component of equitable design.

Broadly speaking, the general public has a positive impression of digital health28,29,30, but only a very small group derives maximum benefit from the possibilities it offers3,31. A review published in 202332 stressed that promoting digital literacy was fundamental to the attempts to encourage the general public to participate actively in decision-making and to pay more attention to their health.

Seeking ways to close the digital gap is one of the main challenges33 facing digital health in the short term. For the most part, it is the over-70 age group that is least likely to possess the technological skills needed or be acquainted with electronic tools and devices, since only 28.5% of individuals aged 65–74 in the EU have basic or higher digital skills, such as the ability to use devices like smartphones or computers34. This level drops dramatically beyond age 75, being just 9.8% in Spain or 4.6% in Italy34. Moreover, a 2023 study of diabetes mellitus patients aged over 65 showed that 85% found digital tools useful, but that no more than 35% actually used them35.

These data highlight the need to address this distance so that digitization does not become a barrier to access to the healthcare system. It will be necessary to think about the situations in which people are most vulnerable (due to the lack of training or the absence of an adequate connection) in order to be able to offer real solutions. The new technologies allow people to consult health practitioners rapidly and directly without the need to come to the health center; this capability is in itself a form of justice, because it provides equal opportunities for patients to receive treatment from health professionals when in other situations it would be very difficult.

The current social and demographic reality is unlikely to change in the coming years. In fact, we believe that it will remain largely as it is, because inequalities will not suddenly disappear, and the trend towards greater longevity is certain to continue. The elderly and the more vulnerable members of the population are generally the main users of the health system and at the same time the ones who are most likely to be excluded by digitization; in contrast, younger sectors of the population or those who run no risk of social exclusion do not face this problem because either they are already “digital natives” or they have digitized rapidly in recent years.

Many population groups—including older adults, individuals with disabilities, people with low digital literacy, language minorities, and those with limited socioeconomic resources—are among the main users of healthcare services and at higher risk of exclusion in the digital transformation. Digital health policies must ensure that these communities are not left behind. This is why it is important to involve them in the design of these digital policies or, at the very least, to take their needs into account when planning the digitization of the new digital health system. The attempts to make access to the digital system more equitable must bear in mind the opinions, experiences, and real needs of this group of people in their day-to-day relations with the health services.

The COVID-19 pandemic made this reality clear, imposing digitization in most areas of interaction between government bodies and the public, and perhaps in the health sector more than anywhere else. The pandemic limited face-to-face access and ushered in alternative modes of delivery of healthcare services such as online appointments, virtual consultations, and telemedicine. All of these services offer significant organizational or management advantages, but not everyone will see these changes as beneficial. In this situation, the principle of justice may be seriously undermined.

Digitization poses the challenge of reassessing the scope of ethics in health. Dilemmas that it raises include the appropriate management of large volumes of health data, the privacy of professionals and patients, and the guaranteeing of equitable access to advanced technologies and virtual resources.