Design, implementation, and evaluation of an online instructional process to enhance teachers’ design thinking skills

Within the scope of the study, an online instructional design based on constructivist learning to improve teachers’ design-oriented thinking skills was developed and its effectiveness was tested in practice. The study was carried out with 6 heterogeneous teams and the teaching process was completed in 12 days, in two sessions of 90 min per day, in a total of 1080 min. This 1080-min online process was designed in the form of large-group and small-group sessions. The total time allocated to large group sessions of this process is 510 min, while the total time allocated to small group sessions is 570 min. The content of the instructional program or learning practices directly affects the duration.

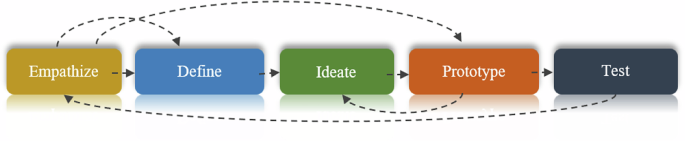

In the study, the design of the instructional process and the work of the teams were carried out by applying the steps of the Stanford University d.school design thinking model (empathize, define, ideate, prototype, test), to help teachers become design thinkers. Throughout the process, design thinker characteristics (Sürmelioğlu and Erdem, 2021) were tried to be activated. In the literature, it is seen that teachings are designed using the d.school model in similar or different forms (Alhamdani, 2016; Benson and Dresdow, 2015; Girgin, 2019; Häger and Uflacker, 2016; Henriksen et al. 2020; Pande and Bharathi, 2020; Rauth et al. 2010; Yang and Hsu, 2020).

Findings on the level of design thinking

The change in the design thinking levels of all teachers before and after the implementation was examined. For this purpose, the Wilcoxon test, a non-parametric method, was used to compare the pre-test and post-test results of the dimensions of the Design Thinking Scale. The findings are presented in Table 3.

The process sub-dimension of the scale represents characteristics of experimentation/risk-taking, creative confidence, holistic perspective, and a dynamic mind, and the individual sub-dimension represents characteristics of innovation/comfort in uncertainty, optimism, critical thinking, and design style, which expresses self-awareness of the person. Statistically significant results were obtained in the process sub-dimension (p = 0.007) and individual sub-dimension (p = 0.022). In this case, the online process has benefited individual awareness. Chesson (2017) introduced the Design Thinker Profile Scale for individuals working in organizations, including dimensions such as personalized solution optimism, visual storytelling, and collaborative exploration. It has been observed that self-awareness is a significant characteristic in the individual’s design-oriented thinking process.

The other two sub-dimensions of the Design Thinking Scale, namely, relationship (human-centered, empathy, reflective, collaborative teamwork) and ethics, encompass an individual’s awareness of their relationship with others. There were no statistically significant changes in the relationship (p = 0.064) and ethics (p = 0.126) sub-dimensions. The lack of significance in the relationship sub-dimension can be explained by the fact that the participants in the study were individuals who did not know each other and met online within the scope of the study. In addition, the fact that the participants were in the occupational group with high social relations (Çelikten et al. 2005) may have limited the change due to the design thinking teaching process. The lack of statistical significance in the ethics sub-dimension is considered important within the scope of the study. No significant difference (p = 0.126) was found between the pre-test median value (4.75) and the post-test median value (5) in the ethics sub-dimension. The answers given to the ethics items of the scale indicate that teachers have a high ethical awareness before the implementation. However, during the process, there were instances where participants did not specify the resources they benefited from and did not explicitly mention their sources of inspiration. This suggested that participants had uncertainties about what was ethical. Despite this, the high scores obtained from the ethics-related items in both the pre-test and post-test indicate that the participants may have been affected by social likability (Erzen et al. 2021; Randall and Fernandes, 1991). The possibility that the influence of socially acceptable and desirable behavior in society could have affected the response to a scale item (Erzen et al. 2021) may have led to the result in the ethics sub-dimension of the design thinking scale.

In the branch-specific examinations, a significant difference was found among social studies teachers in favor of geography teachers in the process sub-dimension of the design thinking scale. Although it was revealed that social studies teachers demonstrated significant changes in the relationship sub-dimension of the design thinking scale and the geography teachers showed significant changes in the process sub-dimension, there was no significant difference between the project teams in terms of design thinking. The individual changes in design thinking levels of teachers did not statistically reflect on the teams. In this case, it can be stated that the process similarly and positively affected all teams, leading to no significant difference among them.

Findings on the quality of products by evaluation type

The effect of the online process on team products was determined by the material development guide evaluation scale. As a result, there was no significant difference between the self-assessments of each individual and the team. Peer and instructor assessments resulted in parallel findings, indicating a difference in the scientific sub-dimension. Significant scientific differences between the teams in which the difference occurred were noted throughout the process. Considering the participant opinions regarding assessment, the cognitive benefits provided by self-assessment (Kösterelioğlu and ve Çelen, 2016; Pala and Erdem, 2018; Şahin and ve Kalyon, 2018) and peer assessment (Şahin and ve Kalyon, 2018; Demiraslan Çevik, 2014; Uçar and Demiraslan Çevik, 2020) for participants who received feedback and those who gave feedback are also observed in the relevant literature.

Three types of evaluation have been made regarding the assessment of the quality of products. These are self-assessments (individual and team self-assessments), peer assessments (individual and team peer assessments), and instructor assessments. Table 4 shows the three types of assessment findings for the materials.

Similarities were observed between the dynamics of the teams in the production process and the dynamics in the evaluation processes. In addition, differences were observed between team assessment and self-assessment in the evaluation processes. In intra-team assessments, three themes have emerged regarding what stands out in more qualified evaluations regarding evaluation through collaborative processes. These themes include the information provided in the content being scientific and consistent, the conveyed information being suitable for the target audience, and the design being original. This finding, as emphasized by Erdem and ve Ekici (2016), can be interpreted as evaluation in collaborative processes transforming from an evaluation based on external criteria that produces comparative data to an evaluation based on internal criteria that produces developmental data.

During the online teaching process, teams have been influenced by various factors. The most significant of these is the ability to use digital technology. The subsequent factors were determined to be the speed of adaptation to the web portal, intra-group conflict, collaboration within the group, communication (messaging on the team forum and online communication), and time management anxiety, respectively. Similarly, Häger and Uflacker (2016) found that design experts, students, and program organizers were greatly influenced by several individuals such as coaches, project partners, competitors, and team members.

During the online process, teams showed two different structures referred to as balanced and extreme based on their working methods and the time they used. Balanced teams completed the planned flow on time at every stage of the process. Extreme teams, on the other hand, either completed their work in a time well below the planned time or used well above the planned time. Lower-extreme teams have experienced anxiety about time management, although they have not exceeded the planned time. It was observed that the primary reason for this is the low skill of the team members in the use of digital technology. The main reason for the upper-extreme team exceeding the time is that the scenario work of the decided idea is done on a ready-made text. This misled them and caused them to do additional work many times. Häger and Uflacker (2016) examined how experts, students, and program organizers at the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design implemented team time management and agreed that time management is necessary. They recommended daily agendas, time counters, and breaks for time management. In their study, designed with a project-based teaching approach with teacher candidates, Dağ and ve Durdu (2011) reported that there were difficulties in time management. Girgin (2019) found that teachers had the most difficulty in empathizing, generating ideas, and time management after design thinking training. Considering these findings and information together with Tsai’s (2021) emphasis that higher-order thinking, interactive collaboration, and time management can be improved with design thinking, time management emerges as both a challenge and a goal for teaching design thinking.

Findings on the effect of the process on satisfaction

Participant satisfaction was measured after the first session of the online process, and it was determined that participant satisfaction was high. In this case, it can be stated that the procedures carried out during the opening, meeting, and introduction process, which is the first event, were very useful. At this stage, the process, purpose, and platforms to be used were explained, the meeting took place, the web portal was subscribed, fun and general culture icebreaker questions were answered in the forum of the portal, and the teachers, who were randomly divided into rooms through the digital platform, were enabled to chat for 10 min in small groups. This situation was also determined by the content analysis conducted on the participants’ opinions on the first activity in the logbook, which was examined to determine the satisfaction of the teachers throughout the process. The satisfaction of the teachers at the beginning of the process also positively affected their satisfaction with the subsequent activities.

To discover how the implementation process leads to a change in teachers and teachers’ satisfaction with the process, logbook comments kept by teachers were examined. Teachers’ statements about what they do, think, and feel about each activity of the online process indicate that they have developed awareness of the requirements of design thinking, and they are very satisfied with the process. Benson and Dresdow (2015) developed a list that captures the essence of students’ actions and behaviors associated with reflective diary and design thinking in the process of teaching design thinking. These are clustered into five categories, consistent with the design thinker attitude: empathy, integrative thinking, optimism, experimentation, and collaboration. In their study, Akkoyunlu et al. (2016) enabled pre-service teachers to keep a reflective diary during the teaching practice course. At the end of the process, participants stated that they had the opportunity to evaluate themselves holistically, monitor their development, gain a critical perspective, and develop a sense of responsibility and writing skills thanks to the diaries, and it was revealed that reflective diaries contributed to the personal and professional development of the participants. Henriksen et al. (2020) stated that there is a need to understand how design thinking can be applied in teacher education, and questioned what teachers understand from learning and using design thinking and found three main themes. These are valuing empathy, being open to ambiguity, and considering teaching as design. As a result, the categories obtained for each activity within the scope of this study are supported by the literature.

Teachers’ views on the teaching process

After the online teaching process, the opinions of the teachers were taken regarding five themes. The first of these themes is teachers’ process-related gains. Gains are clustered into five categories: Design thinker characteristics, design thinking teaching process, animation directing, professional development, and digital technology skills. Girgin (2019) asked why teachers wanted to participate in design thinking training and determined the categories of the responses as a contribution to professional development, and curiosity, interest, and desire for the design process. Teachers’ professional development is crucial to improving student outcomes (Sancar et al. 2021). In addition, Benson and Dresdow (2015) developed products (visual software, graphic design, and 3D models) in the process of developing their students’ design thinking skills in the undergraduate course they designed with the project-based teaching method, and carried out all studies in a digital environment. In the process, students were required to take time to learn how to use digital technology, and the development of their other digital skills (e-mail, learning management system, and virtual classroom use) was supported. The results of the literature and the contributions of the study to the design thinking teaching process were parallel.

Secondly, the contributions of the online process to teachers’ instructional designs were questioned, and the responses were clustered in three categories. These categories are design thinking contributions, animation contributions, and project ideas.

Thirdly, the possible contributions of the online process to subsequent instructional design and technology creation situations were asked, and the findings were clustered into two categories. The first category is individual development (increase in self-confidence towards the use of digital technology, increase in digital technology knowledge, awareness of animation software), and the second is methodological development (roadmap, idea of producing own animation, product release effect with the team). In this regard, digital animation teaching was also carried out in the online process, and evidence was found that teaching was beneficial. It was concluded that teachers have the competence to produce animations individually or together with their students in the next teaching process. In the study of Rauth et al. (2010), it was found that competencies such as prototyping, adopting different perspectives, and empathy developed in individuals after teaching design thinking, and this resulted in confidence in creativity in the participants.

Fourthly, it was questioned whether the branch (history, geography, social studies) teachers who participated in the online process needed this kind of training, and it was determined that they needed such training. When the reasons for these needs were questioned, codes such as the need to embody abstract subjects, the need for visuality, the need for design thinking, the need to design one’s own material, and not being taught in the faculty of education emerged. These results highlighted the need and benefits of both design thinking and animation learning.

In the fifth theme, it was asked what the participants’ suggestions would be to researchers for the teaching process if the teaching process were to be replanned. Two categories have been created regarding these suggestions. These are the teaching process and the entire process. The contents of these categories are as follows:

-

Increased mentor participation

-

Extension of the creation process

-

Teaching two animation software as electives

-

Determination of gains after the ideate phase

-

Including a literature teacher to the teams

-

Rescheduling this training

-

Expansion to other branches

-

Face-to-face training of the same

-

Previous participants mentoring the teams

-

The same participants attend this training for the second time

In the online project-based design thinking teaching process, rich scenario writing, story card drawing, and animation design were taught as learning practices, and all practices were carried out by all teams. In the online project-based design thinking teaching process, the development of products to be produced was supported.