Students pivot to skills, startups, new-age careers

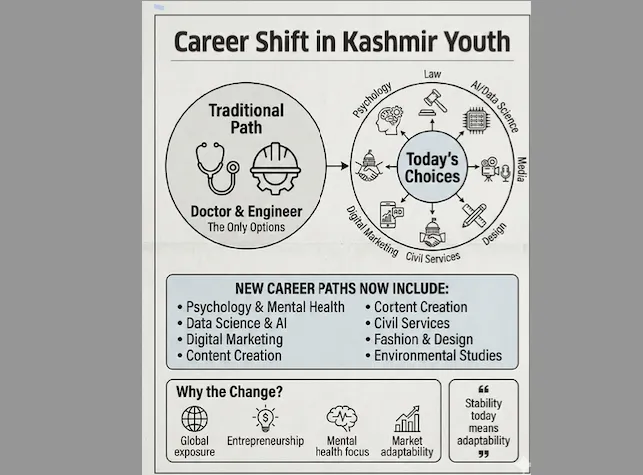

Srinagar, Feb 14: For decades, professional success in many Kashmiri households was defined by two titles—doctor or engineer. The white coat symbolised prestige, and the hard hat promised stability. But a generational shift is underway. Students are increasingly recalibrating ambition around skills, entrepreneurship and emerging industries rather than conventional degrees alone.

Across colleges and universities, more students are opting for psychology, law, design, media studies, data science, environmental studies, civil services preparation and business-linked disciplines such as digital marketing and artificial intelligence. What distinguishes this transition is not rebellion, but market awareness.

“I always scored well in science, and everyone assumed I would prepare for NEET,” said Areeba, a 19-year-old from Srinagar. “But I realised I was pushing myself into something I didn’t love. I chose psychology instead. It was difficult to explain, but I feel confident about my future.”

Students say exposure to global opportunities through online learning platforms, internships and freelancing has reshaped their understanding of income security. Careers that were once dismissed as “risky”—content creation, coding, digital marketing, filmmaking, sports management or fashion technology—are now seen as scalable industries with entrepreneurial potential.

“I think earlier people believed only doctors and engineers could earn well,” said Zubair, a final-year commerce student. “Now we see entrepreneurs, developers, civil servants and creators building sustainable careers. Stability today means adaptability.”

Education observers note that this shift reflects a broader economic transition. The modern job market rewards innovation, digital literacy and specialised skills. Rather than investing years solely in entrance exam preparation, many students are choosing courses that allow immediate skill-building and income generation.

Financial considerations are also influencing decisions. Competitive exam preparation often requires significant spending on coaching and multiple attempt cycles, placing pressure on middle-class families. “At one point, we were spending lakhs on coaching,” said Faizan, who pursued computer applications instead of engineering. “I realised I could build employable skills faster.”

Mental health awareness is another factor. Students today speak openly about burnout and academic pressure associated with high-stakes entrance exams. Career mentors in Srinagar observe that choices are becoming interest-driven rather than reputation-driven. Students increasingly ask about long-term work-life balance, growth prospects and industry demand.

The shift does not signal a decline in the value of medicine or engineering. Instead, it reflects diversification in aspirations aligned with changing economic realities. As industries expand and digital ecosystems mature, opportunities are multiplying beyond traditional sectors.

For this generation, success is no longer a single professional label. It is a portfolio of skills, adaptability and purpose. The ambition remains strong—only the definition has evolved.

By: Jannat Qureshi