How Could My Dad Lose Thousands to an Online Romance Scam?

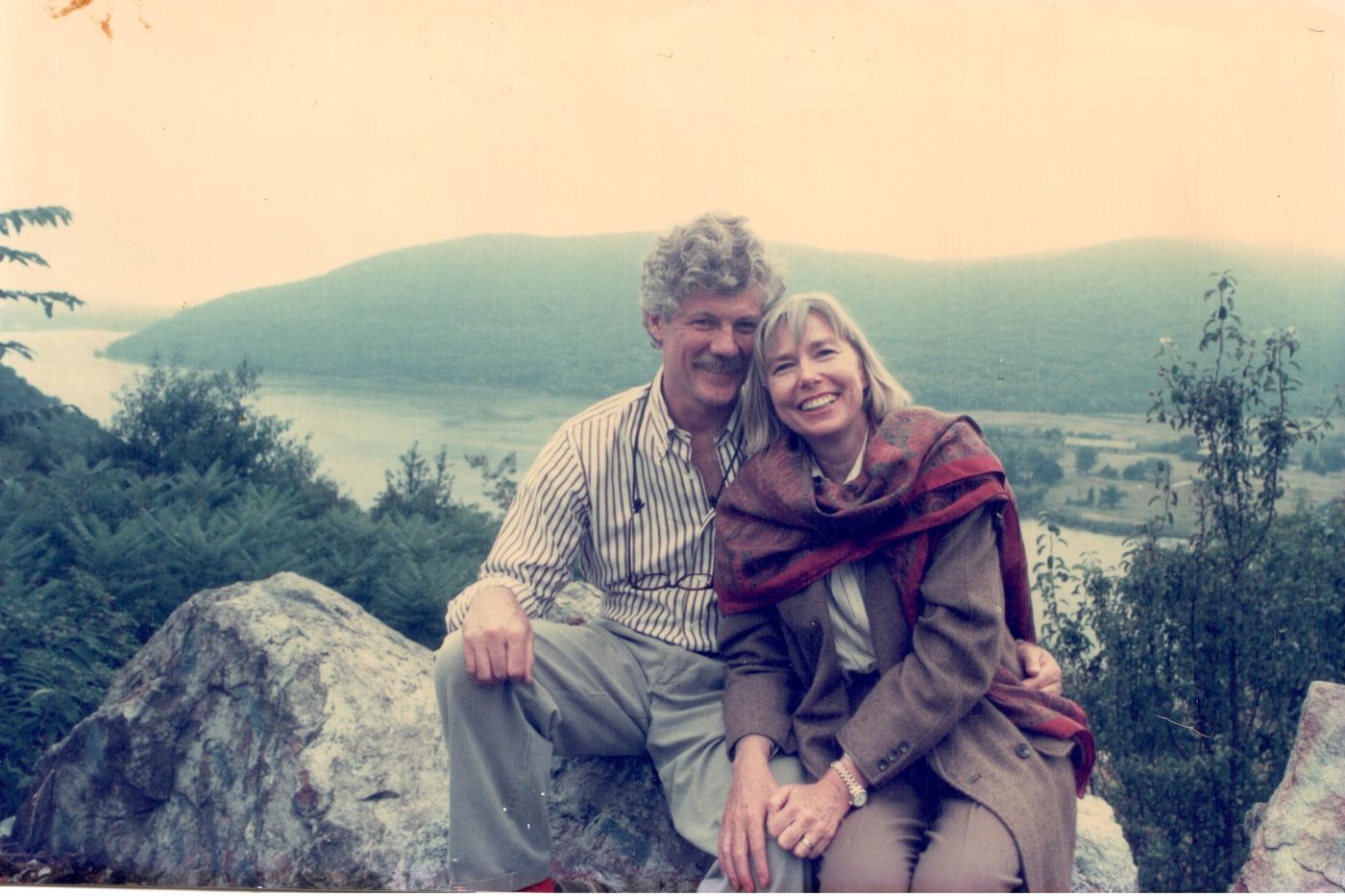

Photo: Courtesy of Christopher Ketcham

This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

It was only after my father died that I got access to his conversations with the creatures who fleeced him. He was so enamored by the members of what he jokingly called his “harem” — women online who may not have existed in real life but who nonetheless ran off with his money — that he printed the transcripts of their dialogues and filed them in metal cabinets in his office in Cobble Hill.

This was in keeping with his diligent habits of organization and documentation. My father, Brian Ketcham, had been a transportation engineer and urban planner of some renown in New York. Upon his death in 2024, the New York Times thought his life and work important enough to run a 1,100-word obituary, in which he was declared an “influential environmentalist.”

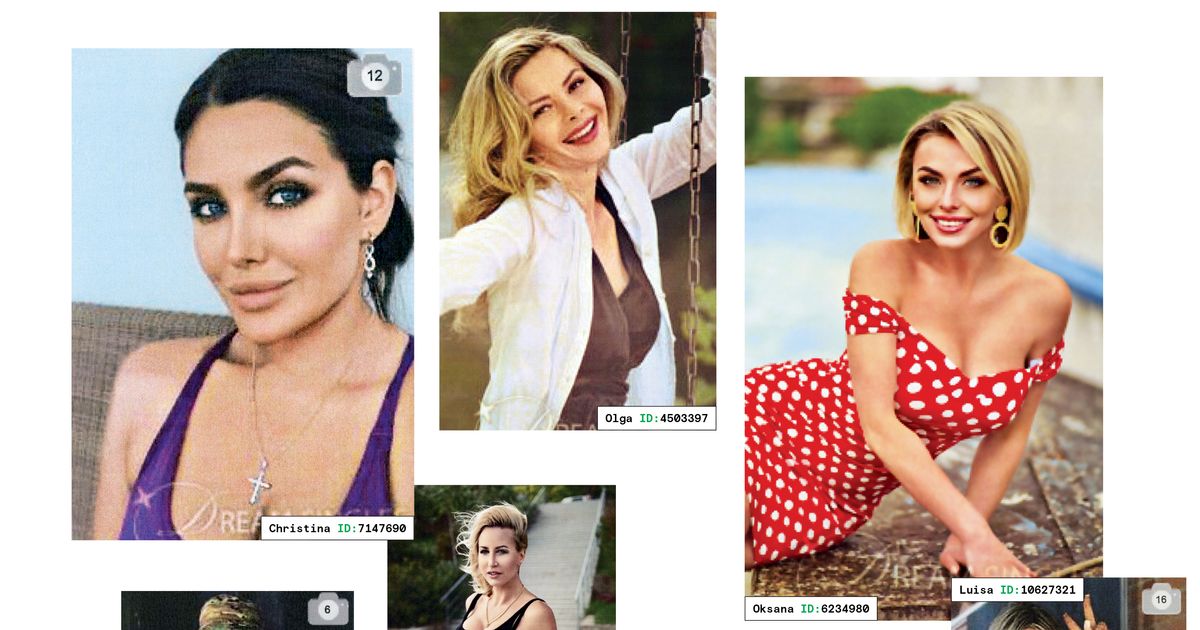

In his 80s, retired for more than a decade, he was spending his days conversing via chat on his office desktop, blinds drawn, with the still image of a large-breasted, smoky-eyed blonde from Russia named Vasilisa — a common name, I would learn later, for striving heroines and would-be princesses in Slavic fairy tales.

According to Brian’s notes, which I discovered not long after his death, Vasilisa, whom he’d met on Dream Singles, a dating website, was five-foot-five-inches tall, 108 pounds. He’d written her ID number carefully on a printout of her profile page. ZODIAC: LIBRA. EYES: GRAY. AGE: 33. What was her real identity? My father never speculated. He believed in Vasilisa. I thought perhaps she was a canny AI bot or perhaps some dude in his mom’s basement in Moscow. There was some slight chance she was a real woman who’d signed up to meet her dream man.

Here’s some of what Brian and Vasilisa had to say to each other on May 3, 2021, the day after he logged in and registered his credit card for the first time. “Brian, after 10 minutes together in real life,” said the woman or man or machine, following an introduction about being “sincere and open” and “wise and sensual,” “will you understand everything about us and our future?” Vasilisa noted that she lived in New York City. My father became excited: She was here, in town, maybe just around the corner.

“I am new on this site. New York City? All other women I have contacted are from Ukraine,” he told her. Already that day, he’d sent messages to multiple profiles. “And, like you, so beautiful. You are perfect. Only I am 82. In good health (you do know the 80’s is the new 60’s). As you report in your introduction if I got to know you for 5 minutes we would be in love. I already am.”

This message in the Dream Singles chat interface, like every one of the hundreds he would eventually send, cost him money. In order to communicate with the women, he had to purchase credits. They were required for every message beyond some initial free exchanges. If you bought more credits at once, they were discounted. On the first day they spoke, my father spent $49.99.

By May 7, he was getting frustrated and flustered and a bit snippy, nowhere nearer his beloved. He asked Vasilisa for a meeting in person. “So … You are in NYC. My family believes this is a scam site and you are just a picture and your comments belong to others. You can prove them wrong.” My sister and I had discovered our father’s venture on Dream Singles almost immediately, by accident, after seeing the name of the site in a series of recurring charges on his credit-card statement.

“Brian,” Vasilisa fired back in a message time-stamped one minute after Brian’s went out, “I’m here not that prove you something, if you don’t trust me we can forget about each other.” (Errors her own.)

“It is to prove this site is not a scam,” Brian replied. “Your refusal just justifies my kids’ belief this site is a scam just using you girls to make money.” Then he got mean: “You might even be paid for each call. What does that make you.”

There was no response whatsoever to this volatile accusation. Instead, as if the exchange hadn’t occurred, the entity on the other side of it continued bombarding him with teasing notes day after day. Robotic in their chipper consistency, mindlessly repetitive, the messages implied nonetheless a passionate need to get together. On May 8, at 4:17 a.m.: “Brian, I need to sleep but I don’t want to sleep alone.” That same day, hours later: “Brian, do you want to kidnap me and spend the whole weekend with me?” On May 9: “Brian, would you like to look into my eyes, hug me so tight and kiss me so sweet?” On May 10: “Brian, how much time in real life with me do you need that fall in love with me?”

By May 16, Brian had tried repeatedly to send her his address in Brooklyn. She never acknowledged receiving it, and he decided that the chat program was somehow blocking it. “I am having computer problems,” he said at one point, to which Vasilisa responded, “Why each man from this site always have a computer problems?”

Seemingly barred in the Dream Singleschat room from sharing his personal address (and later, phone number), he suggested they meet at a public space: the Brooklyn Heights Promenade, a 15-minute walk from his apartment.

“You ask about devotion,” he wrote in his plea for the meeting. “I gave you my example of my last wife” — he was referring to my stepmother, Carolyn Konheim, to whom he was married in 1984 and who had died in 2019. “Our love for each other was intense for 40 years from the day we got together. I cared for her for her last 12 years as she died of Parkinson’s and dementia. Never leaving her. That is devotion. I would show the same love and attention for you should we ever get together.”

But it was not to be. As far as I can tell, Vasilisa did not agree to meet, and they never got together. According to his credit-card statements, between May 3 and May 17, a mere two weeks, his expenses at Dream Singles came to $1,108.98. Eventually, he would spend a whole lot more than that. “As for a real meeting,” he told Vasilisa on May 16, “this site makes it rather hopeless.”

Brian Ketcham with his wife Carolyn Konheim in the early ’90s.

Photo: courtesy of Christopher Ketcham

In the 1963 congressional hearings on “Frauds and Quackery Affecting the Older Citizen,” Ethel Percy Andrus, founder of the American Association of Retired Persons, remarked to lawmakers on the ubiquity of scams and scammers targeting seniors. “Nothing could be more invidious,” she said, “than the pressures that plague older persons and place their health in jeopardy and further deplete their reduced incomes.” The testimonies revealed to the public that an untold numbers of American seniors had been made into suckers. They were cajoled and teased into the purchase of snake-oil cure-alls for arthritis and rheumatism and other ailments, saw their Social Security and disability payments stolen by thieves posing as government officials, and paid out formidable sums for nonexistent real estate. One witness, Paul Rand Dixon, then chairman of the Federal Trade Commission, noted that American society had in its midst a conspiracy of “sadists who have preyed upon the victims.”

The running theme of the hearings was that social isolation and loneliness led the elderly to be easy marks. The choking seclusion older Americans experience today is likely worse. According to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, one-quarter of people in the U.S. age 65 or older are considered to be “socially isolated,” and almost half of adults 60 and older report “feeling lonely.” Access to the internet seems to have aggravated the problem.

Today, fraud that targets seniors is at an all-time high. The FBI reports that losses due to elder fraud — from fictitious tech support, fake investment opportunities, cryptocurrency schemes, and, to a lesser degree, confidence and romance scams — totaled $3.4 billion in 2023. The average dollar loss per victim was about $34,000. In the same year, according to the FTC, romance swindling cost seniors some $277 million, up 16 percent from 2022. Most love-scam victims fit my father’s profile: male, 60 and over, with money to spend.

Among the more depressing phone grifts recalled in the 1963 hearings was the promise of dancing lessons — for which the mark paid in advance — that never materialized. In their desperate “desire for companionship,” said Dixon, “these elder citizens are deluded into the belief that by taking dancing lessons and becoming a regular attendant of classes, they will be able to have an antidote for their cloistered existence.” Those who lived alone, like my father, were more likely to take a phone call from strangers.

I believe it was the slow destruction of his wife Carolyn that pushed my father over the edge. In the decade from the serious onset of her Parkinson’s around 2009, through her development of dementia, and until her death, Brian spent most of his waking hours at Carolyn’s side.

Like my father, Carolyn had had an ambitious career in environmental activism and public service. She was one of the higher-ups under Mayor John Lindsay in the city’s fledgling Department of Air Resources. She’d founded an advocacy group called Citizens for Clean Air that pushed for, and won, astonishing improvements in the city’s air quality. For more than 20 years, she and Brian ran a lucrative environmental and traffic-engineering consulting firm in Brooklyn. When she died, the Times lauded her too with an obituary, declaring Carolyn the “foe of all that befouled a city.” But now that woman was gone, reduced by disease to a husk.

In the later stages of Carolyn’s long agony, by the end of 2016, Brian was so devoted to her that once, when I suggested we share the rare pleasure of a dinner out together and he acquiesced under pressure, he confessed to feeling guilty for enjoying it. He told me never to tell her we had been gone that night. He had lots of help — from home health aides, primarily, and also from my sister, Eve, seven years my elder, who lived nearby and spearheaded Carolyn’s care — but the burden weighed on him nonetheless.He grew old in those years, his weight dropping, his face becoming gaunt. His world narrowed. Friends died or fell away. Carolyn had been the gregarious one, the light around which people gathered, and he was always, socially, her hanger-on. When she faded, so did his community. Brian split their time between their apartment in Brooklyn and their house high in the Catskill Mountains. For a while, in 2018 and 2019, I lived with him and Carolyn in the mountain redoubt. My father and I had good times on the land he owned, taking walks in the rich forest. One of our last long hikes together, years before his death and before his descent into the mania of his screen, was to a towering eastern white pine, one of the last of the old growth, framed in the hazy summer light of the deciduous canopy.

His financial fall started with what he called, proudly, “investor newsletters,” which he discovered while trawling for investment opportunities online. Carnival-barker tout sheets for gambling on stocks and start-ups and crypto is what they were. The newsletter scams, as I came to know them, existed both online and in the form of slick hard-copy packages. Brian defended them as his “connection to what’s really going on in the economy.” One advised an investment it called “the Tesla killer,” which it promised could bring “11,666% gains.” Another I found in his files after his death advertised, in all caps, the #1 BIOTECH TRADE FOR 10X PROFITS; another explained how blockchain technology would “transform our country and generate life-changing wealth.” Still other mailers hawked investments in CBD and, in case of societal collapse, precious metals.

The prevailing tenor was right-wing libertarian, and a number of the newsletters, I discovered, were the mouthpieces of rabid Trump supporters. These greedmongers sought the end of government aid to citizens (especially the undeservingpoor, such bad investors), the sell-off of public goods to the moneyed classes, and the deregulation of every part of the economy so that business could plunder the natural world at will. I tried to express to Brian that he was paying swindlers who backed a president he hated, who hoped to dismantle the very system of social services and environmental protection he had fought for all his life, who would love to foul the air of New York if it meant a penny of added profit. I tried emotional ploys coupled with humor. “What would Carolyn say if she knew? You can’t make money off clean air!” These arguments resonated with him not at all, which shocked me: I hadn’t conceived of the possibility of such indifference. He told Eve he no longer had joy in his life and the newsletters were a petty thrill. It was no small thing for him to say this aloud.

The thrill cost him at least $1,000 to $2,000 a month. His landline was ringing off the hook with offers of opportunity in the markets. I imagined his telephone number had been put in a centralized database with a gold star indicating that here was your primed fool for the taking. He liked the calls; he talked and talked. He was making “friends” of investor luminaries. He never made a cent.

Carolyn’s caretakers became so concerned they alerted Eve. He was spending hours on these calls, they said, and sharing detailed personal information about himself, his family, and his finances. At the time, I found it hard to fathom the satisfaction my father got from yapping with strangers, doling out his amateurish takes on CBD-pill sales and the outlook for crypto and the returns to be made on buying gold. But in retrospect, it was obvious: Someone, anyone, was listening to him as if he were still the important man he had once been. He had a sense of agency, of purpose, and, with his money, a measure of power as he watched his wife’s personality melt and her body collapse and as his own life of hard work and accomplishment receded into the past.

Carolyn died in the autumn of 2019. COVID hit a few months later. Though he had family all around him, he retreated further into the vortex and isolation of his screen. I, my girlfriend, and my two daughters had piled into the house in the Catskills, and together we were growing food, building greenhouses, tilling soil. But Brian was mostly in his study, on his computer. His obsession with the tout sheets led him into a predictable hole, but he never stopped.

Quickly after discovering he’d signed up for Dream Singles, Eve and I figured it for an opportunity for more grifters and told him so. Our father, we agreed, seemed intent on handing his money to liars and thieves. What to do about it? We were clueless. But we knew we needed to track what was happening.

By the middle of 2021, Eve had been covertly surveilling Brian for more than a year, taking pictures of his diary when he was in the shower or out for a walk, rifling through his computer files for documentation of interactions with the newsletter scamsters and the ladies. She stayed busy. She snooped in his emails, bank accounts, and credit-card statements, compiling a record in the piecemeal way she could. She tried to draw him out in conversation. Sometimes, in flights of fancy, he revealed to her that he believed one or perhaps more, maybe two, three, four — who could know? — of the women he met on Dream Singles would be coming to live at his apartment and take care of him. “No one is showing up to take care of you,” Eve told him. “I’m it. Your care. Me. Your son. Your family. That’s it.”

This was received with a look of contempt. “I can take care of myself, Eve.”

Going through his records, she discovered that Dream Singles had a special service for the sending of gifts to the ladies. Brian was generous. In reality, Eve gleaned only snippets of his expenditures. From records retrieved after his death, we learned that in a four-month period in 2023, his purchases for the women included a laptop computer, a luggage set, fruit baskets, and flowers.

But Eve used what she had then to confront him. “You’re not sending anyone anything,” she told him. One night, an old friend of hers, who had known our father for years, visited his apartment for dinner and tried broaching the subject as a joke. “Brian,” she said, “I’ll gladly send you dirty emails if you pay me.” My father had a good laugh at that. There was his old self, for a moment.

Early on in the saga, I thought he would never be so witless as to blow serious money. Maybe a few hundred, a few thousand dollars — sure. It was a distraction, one that would be quickly discarded. Eve warned me that he was headed for disaster. I did not listen.

This, after all, was my brilliant father, the man who’d written New York’s transportation plan to comply with the Clean Air Act. It’s not hyperbole to say that he was pivotal in helping bring about the clear, smogless skies over the city today. Interviewed for his Times obituary, urban historian Nicole Gelinas said of my father, “Brian was integral to New York City’s recovery from the postwar population flight to the suburbs.” He saw “the big picture, that the city couldn’t continue to see the automobile as the engine of the urban future.” Brian, she said, “meticulously drew up the blueprint for how New York would wean itself from its car dependence.” In an email, Gelinas told me, “I think he could not have had the hugely positive impact he had on New York City’s quality of life had he not had his particular combination of personality traits — tenacity, stubbornness, attention to detail, disrespect of authority, and a willingness to explain lots of arcane details to outsiders.”

I admired my father for all this and, of course, for much more. We weren’t close, emotionally — he was not freewheeling with his feelings — but intellectually we were old comrades. It was my father who pointed me down the path of environmental journalism, who had instilled in me love of the natural world and a horror at the wounds industrial civilization was inflicting on it. I still am haunted by the memory of him bursting into my bedroom when I was 6 years old, wearing a gas mask, howling that all of Earth one day would be toxified by the machines we’ve built. (The history of the 21st century, I believe, will prove him right.) At the back of my mind was a persistent denial of the reality that old age had taken away the man I knew and replaced him with someone else, someone increasingly a stranger — tenacious and stubborn in all the wrong ways.

Eve was a tougher animal than me. My sister was disabled, in chronic pain, and the pain had made her a realist and a cynic. It also made her, on her worst days, ill-tempered, prickly, sometimes mean. While at first I laughed at my father’s forays with Vasilisa — and Tatiana, Oksana, Nina — Eve had little patience for the junk excuses and bald-faced lies Brian tried to pawn off on us to explain the incredible disappearing Slavic ladies. It was Eve who got into the worst of the screaming matches with him. And it was Eve who shook me out of my complacency.

In June 2021, one month after Brian signed up with Dream Singles, she coaxed him into a lengthy visit with a neuropsychologist in Manhattan to examine his mental state and cognitive capacity. He protested, grumbling over it, acquiescing partly out of malice: He was going to make the little girl look bad for forcing such an indignity upon her father. The 23-page report that followed the visit found that his working memory and executive function were “below the expected range.” His deductive reasoning was “greatly diminished.” In many ways, Brian still seemed knife-sharp — he could speak at length on the history of Ukraine, relate the latest discoveries in cosmology, and detail the many reasons for his hatred for Donald Trump — but he was on track to lose his mind. In her conclusion to the report, the doctor noted, “There are very real concerns about Mr. Ketcham’s ability to manage his finances and medications independently,” and “it will be important to implement safeguards to ensure Mr. Ketcham remains medically and financially safe.” “It is very strongly advised,” she said, “that Mr. Ketcham and his family speak to an elder-care attorney about putting this in place.”

A long, torturous year followed as we confronted him over and over about these protections. As usual, I was busy with other matters too, deep in my work, beset with writing deadlines and research and interviews, and, like many parents during COVID, faltering in the education of my online-schooled younger daughter. The conversations with Brian about his mental and financial competence ended almost always in bitter acrimony and recrimination. Eve and I seemed to be ganging up on a cornered old man. The experience was profoundly alienating for us all. By turns, my father was glum, indifferent, resentful, and enraged. I said things to him that I regret: “You believe these women are real? That a 28-year-old wants to fuck a man in his 80s? Are you that fucking deluded?” I told him that he was a moron and a dupe and on and on. Desperate, I did something that a few years earlier would have seemed insane: I seized his computer. No matter. He was on the phone with Dell within a day, and within 48 hours he had received delivery, set up a new device, and gotten back on Dream Singles. The man was a rock of certitude. He would not stop. “It’s my money,” he said.

“But Dad,” I replied at one of my lowest points, almost mute with impotence, “they’re not real. None of it’s real. They’re just making a fool out of you.”

Helpless, Eve and I watched. We worried that as he burned through his money, the future of his long-term care was darkening. Eve had no income — she was financially dependent on our father. I was a struggling writer, as I had been for years. We didn’t have the means to provide him with a good life as he declined; we would need his solvent estate to do so. What troubled me most was that he seemed to no longer care about his own future, nor about the future of his children and grandchildren, my two daughters, whom he claimed to love. I had dark moments when I thought I saw in him a kind of nihilistic abandonment of values in the face of his decline, a cowardly retreat into the belief that all life ends with one’s own. His life’s work in environmental protection, of course, was driven by the opposite ethos. How much of the turn away from his old values was due to the fracturing of his mind, and how much was simply a flaw in his character that had emerged under the pressure of age and the specter of mortality? I don’t know and will never know.

Exhausted, without recourse to logic or common sense, my sister and I at last ceased pounding our father with pointless protests. It was then that Eve took the lead to determine what could be done under the law.

The Dream Singles website claimed that the company had been founded in 2003. “With time and effort,” it read, “we have evolved into a leading international online dating agency … We have more than 500 offices in Ukraine and Russia to help you to find your dream love. Our services promote the most genuine meetings, enabling our members to develop endearing and lasting relationships.”

While the company hosted its own glowing testimonials, there were dozens of other stories online, particularly on Reddit, of experiences similar to Brian’s. “I was a member of Dream Singles for 18 months,” wrote one commenter. “I’m too embarrassed to tell you how many thousands of $ I spent there. I’m almost 60 yrs old and thousands of these model type women 20-35 yrs old wrote to me daily. That would have been my first clue that something wasn’t right.” This individual, obviously someone with a sense of humor, claimed to have reverse-searched the images of the women with whom he was supposedly chatting. “I was catfished there first by one of the fake profiles who is a semi well known Russian model,” he wrote. He said he’d found the actual model’s Instagram account and reached out to ask her if she was signed up at Dream Singles. She wasn’t. (The company told New York, “It is impossible to be fully free of impersonator accounts, however we make every effort to minimize such activity.”)

Eve told me the first call she made, in February 2022, was to the Federal Trade Commission, which is tasked, among other things, with the enforcement of consumer-protection laws against deceptive business practices and fraud. She spoke with an intake official who was curt and cold, wanting just the facts. But his voice softened upon hearing the details of Brian’s case. Though it was happening more and more, what my father was experiencing wasn’t a crime. It didn’t fit any current rubrics of fraud or elder abuse. What was needed, he said, was a brutal family intervention.

By the summer of 2023, Eve had asked several elder-care attorneys about the possibility of taking our father to court on charges of incompetence, barring him from burning through more cash. One attorney told her that filing the initial suit would cost us $10,000 — money that neither of us had — and that if our father countered, which I expected he would, we’d need to find yet another $10,000 to fight him before a judge. Every lawyer Eve spoke with offered the same opinion: Given that he presented well, even as his mind faltered, winning in court was unlikely. Brian would have to agree to yet another psychological exam, which he had the right to refuse — and which, given his recalcitrant character, he would. His doctors also recommended we drop the idea. As doctors generally are, they would be reluctant to testify against him in court. (It was a healthy hesitation, given common abuses by greedy kin.) If we moved forward with legal action, it would likely do nothing more than alienate us further from our father, cataclysmically so; it would devastate him and us.

After his death, I called up a well-known elder-law attorney, Amy DeLaney, to get another assessment of my father’s case. She confirmed that Brian’s experience, in the age of screen connectivity, was increasingly common. She recalled the story of an elderly couple who had come to her for help, the husband dragged in by his horrified wife. The wife said the husband was the victim of online fraud. He believed that he was corresponding, via email, texts, and Facebook, with ’80s alt-rock star Edie Brickell, wife of Paul Simon. Edie had claimed to be in desperate financial straits. The husband believed her, and Edie began hinting at a romantic connection. The man was hooked, and out from his bank account into hers went thousands of dollars. “To meet him,” DeLaney said, “you would not think anything was wrong with him. He went about his life just like any other person. He could handle all his own activities of daily living. But something in his brain told him that Edie Brickell was in love with him.” (Edie Brickell, if you’re reading this, was that you?) The wife wanted to put their accounts in a protective trust, safe from the con artist who’d ensnared her husband in this fantasy. A believer to the end, he refused. The wife hung her head. There was nothing DeLaney could do to help her, or him.

When I asked DeLaney about the possibility of suing the women from Dream Singles in civil court, she said “sure,” but how would you even engage them in a lawsuit? And how would you prove a fraud had been committed? Positively proving it would be nearly impossible.

What about a class action of people who felt they’d been cheated, I asked, a gathering of the many prospective claimants from the online back alleys of Reddit? It would have to surmount the same hurdle, she said. The hustlers might never face a lawsuit, much less justice.

In the spring of 2023, we noticed a change in Brian that seemed to be for the better. He had sold the upstate house for a good six figures and was flush with cash. Long a homebody, he was going outside more, for walks, he said, and for “other things,” about which he smiled knowingly with a bounce in his step. What he was trying to keep hidden was that he’d met a number of new women on Dream Singles who, at long last, had expressed a willingness to meet in person in New York.

Eventually, Eve and I learned that among the ladies was 37-year-old Ekaterina, who was opening a beauty salon on Madison Avenue and who happened to be staying at an apartment in Brooklyn, not far — incredible the coincidence — from Brian’s place. He was very pleased. (When reached for comment, Dream Singles claimed that Ekaterina lived in Poland and that she’d never said she lived in New York.)

They planned first to meet at the Met, but she was a no-show, as he would later admit to Eve. He waited in the echoing vastness of the museum’s Great Hall, expectant, then worried, and finally dejected and feeling worse than ever. He had no way to call her — he could reach her only via the Dream Singles portal for the usual fees.

Brian told Eve that not long after the trip to the Met, Ekaterina explained her absence: Her best friend had been hit by a car on the day they were supposed to meet. Eve soon ferreted out the tragic details. The best friend’s mother had then come to visit, and the mother had then had a heart attack. It was a busy time for Ekaterina.

Brian and Ekaterina had many exchanges about why she kept failing to appear in the flesh. Ekaterina couldn’t find a cab. She got the flu. She got COVID. She got robbed by two men on her way to meet him. Also, she was busy prepping to open her new salon. The salon was called Valkyrie. Eve told our father no record of such a business existed. He wouldn’t have it, didn’t believe it. He said he’d be there for the grand opening of Valkyrie.

During that spring and into the summer,my father went to meet not only Ekaterina but numerous other women on Dream Singles. He waited in bars, restaurants, hotel lobbies, sometimes for hours. We told him to stop this madness, but he refused. He contracted COVID on one of these sojourns. Again and again, following the missed meetings, he reached out to the women, every word of his concern and worry and hurt dinging his credit card. He received more absurd reasons for not getting together, and he continued to object — mildly, uncertainly — as he had since his first encounter on Dream Singles with Vasilisa two years earlier. Yet he continued on. He remained so hopeful that, at about this time, he started calling around to hotels in Downtown Brooklyn, near his apartment, and typed up and printed forensic notes on the qualities of each. The Nu Hotel, two blocks from his door, was “rated very good, but basic, small, no glitz,” and so on. I was reminded of the dictum that insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. In a message to one of the women, Inna, Brian wrote that he had often found himself on the side of lost causes. There were things “worth fighting for,” he said, “even if the effort seems hopeless.”

In the space of three years, Brian spent, by our estimate, at least $45,000 at Dream Singles. In return, alone in his apartment, he got heartbreak, sorrow, agitation, anxiety, a more desperate loneliness, and collapsing relations with his children. Only his death stopped the hemorrhaging of cash.

The end came with a catastrophic fall this past August. A blow to the head and spine, from which he was dead in an intensive-care unit in Bellevue within the week. I was gone in Europe, on assignment, but came rushing home and was at his side with Eve for his last breath. It was the first time I’d seen someone I love die before my eyes.

In the months prior, truth be told, I had given up on my father, relinquishing him completely to his fantasies. After his death, I was full of resentment — which is to say, I was reacting the way a child would to a parent not being there as the child wants. Reading through the files in his office, I saw that Eve and I had not been as forgotten as it had seemed, and the knowledge burned. To Olga, he’d written, “I have a lovely daughter who dotes on me and a son who is a brilliant journalist.” He spoke of my children, our dog. I saw words shining with love, reaching out from the page.

Maturity demands that we look at the world as it is: My father was preyed upon in a state of terrific fragility by ruthless people. There was nothing Eve and I could do to stop it. And yet we felt ashamed and guilty. Amy DeLaney had told me this was a common reaction among the children of the scammed. She said it had led many families to never speak of the experience of seeing their loved ones duped and exploited. The silence, of course, only benefits the predators.

I had wondered to DeLaney if an article such as this could draw out from the shadows other men who’d become targets and if it could lead to litigation and perhaps even criminal prosecutions. What I really wanted was far more severe. I imagined retribution — salutary daydreaming I should keep to myself. But likely there would be no penalty of either kind. What happened to my father would occur again and again.

In the meantime, until the day I die, I will remember the women of Dream Singles for having committed an offense for which there really is no proper punishment: stealing a portion of an old man’s soul in his twilight years and making him, to his family, a living ghost.