The Black University and Community Currencies, PT. 2

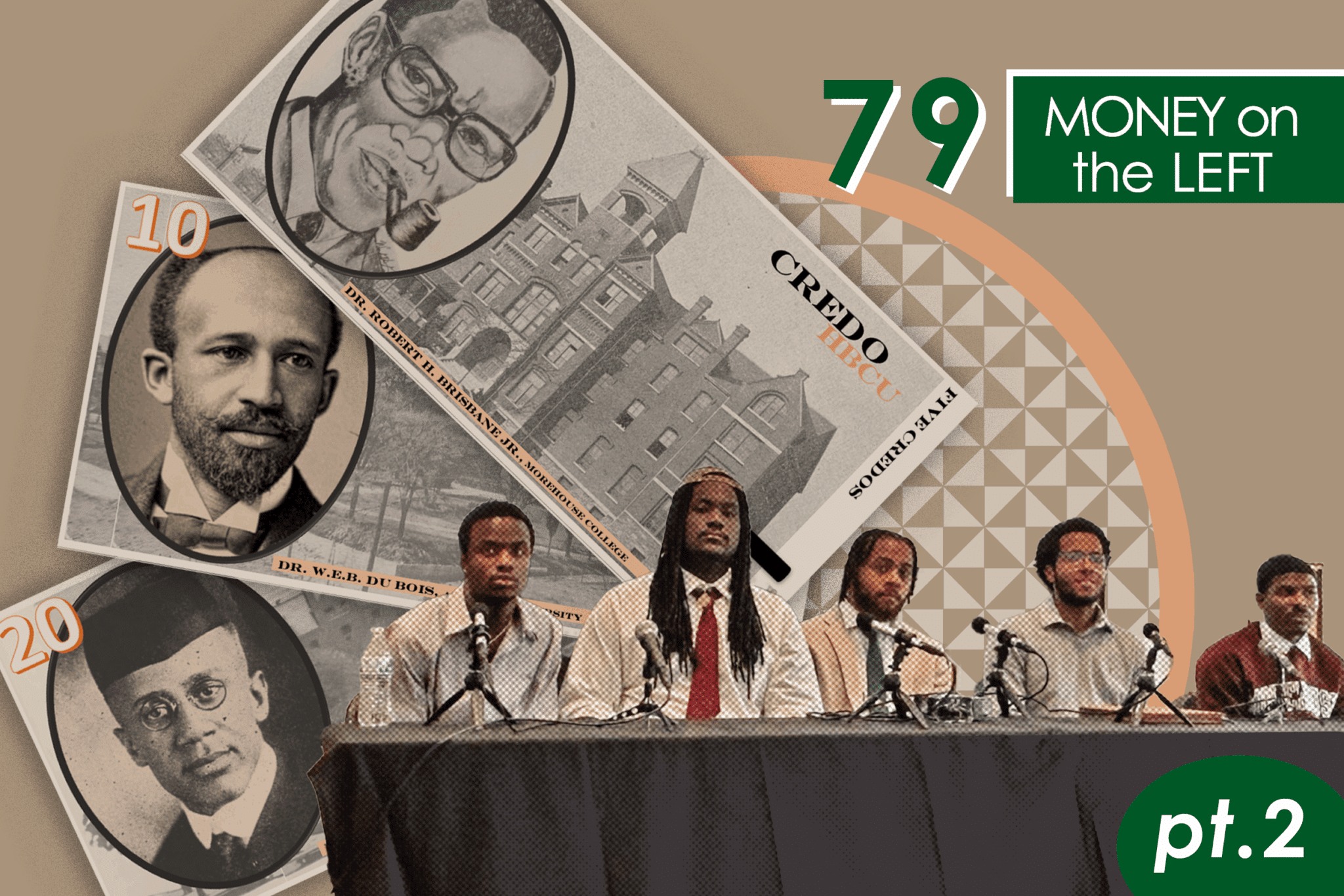

In this episode, we share Part 2 of our coverage of The Black University & Community Currencies workshop (Click here for Part 1). Held April 25, 2025 on the campus of Morehouse College, the workshop fostered dialogue between students, faculty, and activists about the radical possibilities of public money for higher education, broadly, and for communities at and around Morehouse, specifically. The occasion for the workshop was the conclusion of a semester in which students enrolled in Professor Andrew Douglas’s advanced political theory course at Morehouse implemented a classroom currency called the CREDO for use by Morehouse students.

In practice the CREDO bears close resemblance to complementary currencies like the Benjamins at SUNY Cortland, the DVDs at Denison University, and the Buckaroos at University of Missouri, Kansas City. One significant aspect that sets the CREDO apart is that it is the first we know of to have been implemented at an Historically Black College or University. Another unique attribute of the experiment is that students were invited–and very capably answered the call–by their professor to reflect publicly on their experience as users, advocates, and critics of the currency at an HBCU.

In the first half of this two-part episode, we hear directly from Isaac Dia, Elijah Qualls, John Greene, and Bruce Malveaux–students at Morehouse College and participants in Professor Douglas’s advanced political theory course–about their experiences with the CREDO and its implications for the Black University concept. This part has been transcribed below. In the second half, we hear audio of the panel itself as it took place on April 25, 2025. Both halves of the episode reward close attention. Together they document a moment of substantial conceptual and political advance for public money theory and for the hermeneutics of provision.

A very special thank you to Isaac, Elijah, John, Bruce, and all others who participated in the panel discussion and interview.

Visit our Patreon page here: https://www.patreon.com/MoLsuperstructure

Music by Nahneen Kula: www.nahneenkula.com

Transcript

This transcript has been edited for readability.

William Saas

Welcome to Money on the Left. It’s really nice to have you. As a way to kind of kick things off, what is the Credo?

Elijah Qualls

The Credo is a currency that we established in our political theory course over the span of the semester. We did various tasks and jobs where we could accumulate the Credo. Primarily, this was done through community service. However, there were other events on campus that were approved through Dr. Douglas that we could also accumulate the Credo through.

This was all with the purpose of accumulating 50 Credos to pay our taxes at the end of the semester. The entire idea and purpose of the Credo was to mobilize labor that would not have otherwise been done by students.

William Saas

Can you just sort of walk me through all the different ways you can earn them?

Isaac Dia

I feel like that was the freest way you could ever earn a currency. It was like, whatever you did, you could pretty much get a Credo. You can either do the community service, you would fill out a paper and for every hour or every certain amount of hours for community service, you would get a certain amount of Credos.

You could buy Credos. Some people would pay $20 for 20 Credos. Some people pay $5 for 20 Credos. It’s just whatever they decided. Or you could either raise your hand, answer a question, and then they might give you between 5 to 50 Credos for whatever you answer.

William Saas

Andrew, was that built in or is that more of an informal thing that Isaac, you and other students developed yourselves?

Andrew Douglas

Oh, no, that was an informal thing. I consulted mostly with Ben Wilson – and I’m going to blame Ben Wilson – ahead of time, because he’s been doing this up at SUNY Cortland. I basically followed his model. The only officially sanctioned mechanism through which one could earn Credos was by doing community service, but they could do whatever community service they wanted to, they simply had to have their site supervisor fill out a form, indicating what work they did and how many hours. I would pay them on 5 or 6 pay days over the course semester. Then the private sector just emerged organically, and it turned out that we had a couple of students who did a lot of work well beyond what was required to earn enough to pay the tax.

They began to do business with their fellow classmates. It seemed like the private sector was flourishing in our classroom.

John Greene

If I could jump in, the special thing for me about it was kind of seeing the birth of a currency and seeing the way that a currency comes about, the way we read about in Moral Economies of Money. You have the government that establishes the demand and then they spend money on incentivizing certain labor, and then all of the money in the economy is coming directly from doing labor that is, ideally, democratically decided. Although, we never got around to actually voting on what we wanted to incentivize like we had planned.

The idea being that, in a fundamental sense, when you have the government printing the money that is circulating in the economy, ideally, is coming directly from this labor that was incentivized by the government on a democratic basis. I thought that was very interesting and, to that point about the educational aspect, really showed exactly what we were learning about in some of our readings.

William Saas

Another theme of the panel that was recurrent, and I think, Isaac, you brought it up explicitly early on in the discussion, around the capacity of the Credo and the Uni and the public money perspective to educate. In your case, I think you say the best thing the Credo did was help to educate you about how money works.

It could educate others how money works. With the US dollar, people have been educated for a very long time, through their whole lives, more or less, that money is kind of an alienating and alienable object. We come to be suspicious of it. It is the root of all evil. It is this thing that we want and revolted by at the same time.

Can you talk to us about your experience of using the Credo? Did it feel like that to you? Was it a reinforcement of the education every time? Or was there, experientially, a moment where you felt like you might be falling into that kind of common experience of using money and having attitudes toward it that might resemble your attitudes towards the US dollar?

Isaac Dia

This was the one thing I was talking about during the panel. I feel like there shouldn’t be a tax for the Credo, because then that gets back to how we felt about it originally, where it is kind of transactional, where you feel that burden. When there was like a week left in class, that’s really when that private sector started to flourish because everyone was like, “oh my God, I’m like ten Credo short.” That’s when people were paying $20 for Credo. I think if we were to implement it into the real world, we could come up with a better idea for how we could get the Credo back and make sure so many people don’t have it as much instead of creating a tax.

I know a lot of kids wanted to do a tax for the end of the year, like that’s how you would graduate. I feel like that just creates more of a burden, where you start to see the Credo like a regular dollar and you’re like, “I’m only doing this so I can graduate. I’m not doing this because I really enjoy it. This is just another burden we have.” So that would be my only thing – to get rid of taxes.

Bruce Malveaux

I have a counter. I think the tax is necessary because if no one had to go get it, I’m not sure many people would. It’s also deeper than just a tax. For me, it’s more like serving a community, because that’s at least what Morehouse was built off of and Morehouse got so far away from serving its community.

So, I’m a fan of the tax. If it does get bigger, I wouldn’t mind the Credo being a community service graduation requirement. It would be how many Credos one needed to how much community service was required. Some majors are pretty deep and don’t have as much time as business majors, for example.

John Greene

Yeah, I would argue that the tax was kind of the entire point. The Credo is supposed to be a way of incentivizing labor that wouldn’t otherwise be incentivized and the traditional way of doing that is always coercion. In this case, failing the class is the power we have.

In the case of governments, it is violence and throwing you in jail, or whatever that may be. As much as the coercive aspect of the system is an ideal, in our classroom or in government and in capitalism, I think the entire point of the exercise is to attempt to emulate that, to incentivize labor that we wouldn’t otherwise be doing.

Elijah Qualls

I think I agree with what you guys are saying about the need to incentivize people. For me personally, I didn’t have a base incentive to do the labor this semester. The reason why I did accumulate the Credo was because there was that tax at the end of the year.

However, the reason why that tax was established was because there was not some larger market that we could operate in. We didn’t have any other way, yet, to use the Credo. We couldn’t buy things on campus with the Credo, and we didn’t even get to the point where we could use the Credo for extra credit.

If we start adding those other kinds of ways, I don’t think it would be a coercive method. I think it would be a more cooperative means of incentives. It wouldn’t be “do this or else,” it would be “if you do this, then it opens up the opportunity for you to purchase other things.”

Especially if we do extra credit that could cross over to other classes. I think that’s an easy way to get rid of the necessary taxation and more so drift towards a market, and then people will have an incentive to accumulate the Credo, because then they can use that in the market.

John Greene

I feel like that’s a question that we had throughout the class that we never fully answered. That being, every currency that we’ve ever had has been backed by the monopoly on violence that the government has by some sort of coercion. But we also brought up the idea that, in the current era, is that even why currencies continue to exist? If taxes disappear today in the United States, would people stop using the dollar?

Will we no longer have a need for the dollar? You could kind of make arguments either way, I guess. It’s interesting, because it doesn’t feel like the tax is really the most important thing once you have a currency off the ground, but it’s also never really been tried before, as far as I know.

That’s more of a question for you guys. What do you think?

Andrew Douglas

I’m happy to jump in here. From my perspective, the great failure of the experiment was that we never really got around to democratizing monetary design. I, as the sovereign initially, created the exercise and we never really imposed the tax, imposed the terms for acquisition of the Credo and ideally, we would bring everybody into some conversations and some decision making over what that would entail and what that would look like.

I suppose it was almost impossible to do that in the first run of this experiment. If we get it up and running, if we get a couple of professors buying in on a semester-by-semester basis, we could really begin to democratize some of the decision making around that. But coming back to the tax piece, we did have some very rich conversation over the course of this semester about how the tax obligation might begin to feel different or be experienced differently than it is in our day-to-day existence as US citizens who pay taxes where we feel and experience it as a burden and transactional. It might be experienced differently if we’re actively involved in making decisions about how we’re going to use the currency, what kind of work we’re going to promote, how we want to incentivize labor and engagement in various sorts of projects on and around campus. If we really buy into that, the idea of paying back a certain portion of that at the end of the semester feels less like an obligation and more like an exercise of our agency.

We did have some really interesting conversations around that in the abstract, even if we never really got to the point where we could begin to democratize that tax obligation, that element that drives the currency in a certain respect.

William Saas

I run a similar kind of class, but we sort of live in that design part. We do the public money sort of orientation, and then we get into actual monetary design on campus, if we had to – in fact, students have to – design a currency to fill a gap to, to serve a need, and to serve a purpose that isn’t currently being served or is underserved by the current monetary regime.

What would that look like? Students put together their proposals over the semester. This last time I taught it, one of the more illuminating things for me was to realize how much competition our designs would have, or do have, already on campus. I was kind of delighted when I was going back and listening to the tape because this didn’t show up so much – I don’t think we heard it in the panel – but I think someone, probably someone on this call – I couldn’t quite pinpoint the voice – said, “I want to talk about getting rid of the BEDC or something like that.”

Elijah Qualls

Yeah, the DCB.

William Saas

DCB okay. Somebody said under their breath, and we never ended up talking about it, but I suspect that it’s something like competition for the Credo or would be, prospectively. What is the DCB, what does DCB stand for and what is DCB in practice?

Bruce Malveaux

I don’t know what DCB stands for, but it’s basically like a campus dollar. You buy in and they give you X amount of dollars. It’s tied to your meal plan. I don’t think you can buy DCB outside of a meal plan. So, you buy the meal plan, and they give you X amount of DCB to go to the campus store or eat at the food spots on campus.

Elijah Qualls

We talked about this a couple different times in our class as well. I’m not sure if I was the one who said that or not, but I do support that notion. I think the Credo should replace the DCB because the thing is, it comes as a part of whatever meal plan you will purchase at the beginning of the semester.

There’s no way to accumulate more after that. Right? Say you come in as a freshman, you have to get the unlimited plan. I believe that comes with 230 DCB’s. That’s a 1 to 1 transference with the US dollar. I think things are a little cheaper if you purchase with a DCB rather than using your debit card.

Where I think the Credo would be more beneficial is, according to the plan that we have set up here, you can accumulate the Credo by doing certain things. For example, you know, again, the most surface level thing would be doing community service, right? However, towards the end of the school year, we began exploring some other ways that you could accumulate the Credo, but those could all be explored and expanded upon.

The benefit to that is now you could use the Credo to buy things on campus just as you would with the DCB. And again, that goes back to what I was saying earlier about the market for the Credo. This would then create an incentive for people to accumulate the Credo and then, of course, conversely, that would mobilize labor and have more projects done that originally were not getting done.

William Saas

Thank you. Anybody google, in the meantime, what DCB means? What does it stand for?

Elijah Qualls

I’m trying to Google it, but I cannot find the definition for it.

William Saas

This is perfect because I’ll say – while you’re doing that – at Tulane, we have at least three. There’s Splash Cash, which basically anyone can buy in and you just get dollars on your ID card. Faculty, staff, students, everybody can do that. Then there’s Wave Bucks, which I think is a lot more like the DCB meal plan oriented buying stuff at the student convenience store, stuff like that.

Then there’s Nola Bucks, which to me seems novel to Tulane, in some way, which is cash that the university forces you to buy and are only redeemable at certain businesses in the community. It’s meant to be spent at the local Domino’s, which was one place we discovered.

But then, of course, it’s used so infrequently that the local Domino’s is like, “what are you trying to pay me with here? What is this? Nola Bucks? I don’t know what this is,” because they have a lot of turnover or whatnot. Anyway, in any case, for your class, Professor Douglass is the sovereign, but then we sort of exist in a hierarchy where there is already a complimentary currency or a community currency at Morehouse, which is more or less just a straight 1 to 1 with the US dollar, with a little bit of a discount and probably compulsory for those who live on campus.

I wonder, it seems like there’s some productive problem space here to investigate, as my colleague Scott Ferguson would call it. We have these competing currencies on campus; how would we reckon with them in implementation of our own?

Bruce Malveaux

Oh, I was going to tell you, at Emory, if you don’t spend it, they give it back to you. Morehouse is a one of one. A true one of one.

William Saas

So, no getting it back.

Bruce Malveaux

No getting that back. I actually had a problem, I had too many DCB’s and started giving them away. My friend and I actually had too many DCB’s, so we went to Slim and Huskies and we just bought almost all the pieces and we gave them to the homeless.

William Saas

That’s great. Come to think of it, I just went to our student store and the shelves were pretty bare because, I think students loaded up on stuff with their surplus Wave Bucks at the end of the semester. Just to say, “I’m spending this money. You’re not having it Tulane.”

Andrew Douglas

Yeah. I was just going to add, I often wonder how helpful these sorts of competing currencies are in terms of getting folks to think about money and complementary currency in the way that we want to, because it’s simply a way for the institution to guarantee funding. Basically, it acts as a way to force students to pay upfront so that the college can budget and finance over the course of the semester and the academic year.

The college is operating exclusively in a kind of orthodox monetary regime sort of way, a capitalist de-risking sort of way. The students experience it in a negative kind of way as something that’s imposed on them without any agency on their part. It’s the antithesis of the kind of democratizing work that we’re trying to do around complementary currency creation.

I think it’s important to get students to realize that these complementary currencies are already functioning all around them. But at the same time, I worry that because people’s experience is already so negative with them that it may actually be counterproductive to the work of trying to imagine otherwise.

William Saas

I think you’re right. What I find interesting and where our discussions went in our class around these things was around the concept of seeing an infrastructure that’s already in place on campus that, if one were to be sort of revolution minded, one could be driven to try to operationalize that to serve your project or our project.

I think you’re right that it’s a mechanism to capture money from students in advance and probably stash that in a savings account. They start earning interest on it immediately before you even get to campus. But something like Nola Bucks here, and maybe this is unique, it’s already an attempt. It has a kind of ethos of community participation built into it.

There is an infrastructure, and there’s at least a rationale or an argument that we could take to the administration to say, “hey, look, we want to build this out in these ways.” I’m not so sure that the other ones aren’t there and so, Andrew brings up a great point. There’s a lot of negative feeling around these campus currencies that are already in place.

What do we got? What can we do with that?

Elijah Qualls

I was going to say, with a lot of these conversations, the notion that I had for a majority of the semester was that those at the top should really be pushing for programs such as this. Our board of trustees are the ones who should really begin this movement.

Then I started to realize they don’t really have, in my opinion, a reason to want to support this. I think the best way for this to really begin or to gain traction at Morehouse is for it to be a bottom-up sort of approach.

We create an alternative to the DCB, show that it’s working, show that it has external benefits and validity and applicability. Then, maybe at that point, those higher up who have a say so in the infrastructure at Morehouse College would then see the benefits, because I do think Morehouse is very interested in its external image.

A lot of its revenue, particularly from admissions, comes from image and legacy. One of the great things one could do for your image, especially as an HBCU, is to create some sort of currency that is feeding off of that Afrocentric mindset of helping each other with the sense of community and building each other up.

Morehouse College being at the center of that would be pretty – revolutionary seems a bit hyperbolic – but pretty impactful and pretty powerful to see. I think that would bring a lot of attention back to Morehouse. I think that’s where the higher-ups vested interest would come from. It would come from an increase in popularity through a program such as this that started with the students.

I think the students need to show that there is an incentive on a large scale for something like this.

Isaac Dia

What Elijah was talking about with the image is true. I think a really easy way to get them to care about the image where you can kill two birds with one stone, where we can help the community and we can better Morehouse’s image is with the restaurants we already have on campus.

They kind of do this at Georgia Tech. That’s the only reason I know this. They have Buzz Cards, and with those Buzz Cards students can go to local restaurants, like Moe’s. I think it’s like Moe’s, Waffle House, and maybe Buffalo Wild Wings or something like that, where students can use their Buzz Card. It’s their version of the DCB. they can go there, and they can scan their card there.

Now they’re eating really good food instead of the school cafeteria. I think if Morehouse wanted to improve their image and help the community, we could have more local businesses, like Slim and Huskies. There’s a Slim and Huskies on campus and there’s a Slim and Huskies five minutes away from campus.

I think Morehouse should partner up with them where, if you’re just out and about and you stop with Slim and Huskies, you should be able to swipe your DCB card and you should be able to eat Slim and Huskies with your DCB card, because what’s the difference between that one and then the one that is out in real life?

I think if they were to work with more local restaurants to provide better meals for kids, that’d be a great way to help the community and improve Morehouse’s image and the students win. It’s a triple win for everybody.

John Greene

I agree with ‘Jah. I think that’s kind of the crucial thing. It would have to start with the students. With the Nola Bucks, it seems like the school has a vested interest in attempting to get the students more involved in the community outside of campus. I feel like Morehouse has kind of the opposite attitude.

I feel like we all have stories of people telling us and the school telling us that they don’t want us to go off campus. That it’s dangerous out there, and if you do leave, you should make sure you bring somebody with you. Don’t be out there by yourself. I volunteer with Midnight Riot on campus where we walk around, and we’ll pick up trash in the community.

As we go, the students who run it are always pointing out, “Oh, yeah, Morehouse owns this plot of land. Look at it. Look at all the trash that’s all over it. They don’t take care of it. They own this land over here, but it’s covered in trash.” I think it would have to start with the students. It has to be because we wanted it, or because the faculty wanted it. It would have to be bottom up to the point where, for the board of trustees, it becomes in their best interest to put their money into it; otherwise, I don’t think they ever will.

William Saas

It seems like something like Midnight Riot and organizations like that could also be interesting, existing social infrastructure to tap into where there’s already activity off campus when you’re being told precisely not to go. I would imagine they’ve had to make a pretty persuasive argument to do the work that they’re doing. Credo, and when the way we’ve been talking about it, is not about destroying Morehouse as it exists and building something else whole cloth. It’s not it’s not revolutionary in its current iteration. That’s good because, you know, you go to Morehouse, but there is maybe something more transitional at play. I love the bottom-up emphasis that was present in the panel and it’s present throughout our conversation here. Are there other infrastructures on campus that you could point to and tap to help break down those barriers?

Elijah Qualls

We already have some infrastructure in place that does focus on outreach and betterment of the community. I know we have prison education pipeline programs in place. I wouldn’t be the first to tell you about these because I’m not involved with them, but I know they exist, and I know they’re good programs that do quality work.

I believe Judge Murray and the political science department at Morehouse College is pretty involved with that program, where they go into the prison system and they work on educating some of the inmates there and things like that. That’s one thing. I also know our Bonner Scholarship at Morehouse College is one of, if not, the most prestigious institutional scholarship that you can receive.

It’s a full ride scholarship. In exchange, the students who receive that scholarship have to fulfill a certain amount of community service hours to maintain that full ride scholarship. Outside of that, there’s an expectation for every single registered student organization that they fulfill a certain amount of community service hours. My organization just filed to re-register as an RSO.

One of the things that you have to submit is your community impact, like how many community service hours and things like that. You’ll see in certain areas here and there an interest in giving back to the community and improving the community. However, those are select cases. While those are multiple examples; we have a lot of RSO’s and the Bonner scholarship is pretty large, it is still not enough. It’s not like this is a campus wide thing and I think that’s where the Credo would really come in. That kind of separation and destruction of the wall that divides us is also very important, because right now our community service comes from a subconscious place of, “I’m in a better position than you right now, so I owe it to you to give back to you.”

I don’t think we’re even scratching the surface of the potential of what a mutual exchange could look like. Right now, I think a lot of students at Morehouse think, “I’m at college. You’re not. I’m going to give back and help you.” However, they don’t come at it at all from a place of, “how can you also help me?”

I think there is potential for a mutual exchange. The last point I wanted to make was how you mentioned the Black University, and whether or not Morehouse needs to be completely torn down and built up anew or can it just be restructured? If we’re looking at the most earnest idea of the Black University, I don’t think Morehouse can be that.

I think that Credo is also an opportunity to improve Morehouse to get closer to that Black University concept. I don’t think Morehouse should ever be destroyed by any means. I think Morehouse does need to take some time and reflect on what it’s doing right now, because I think it’s rapidly losing sight of its original mission.

I think that Credo will help the students to really understand what we’re about. Morehouse should not be about wealth accumulation, in my opinion, as a humanities major. I don’t think that all the students should just be focused on accumulating a gross amount of wealth.

I think it’s got to be something completely different as Black people looking at how our predominantly Black communities, such as the West End, are doing right now. I don’t think wealth accumulation is the only way and then you just expect to give back your money. I think it should be something more focused and skewed towards the betterment of the community and the public benefit rather than the fiscal or the monetary benefit.

John Greene

Kind of on that same note of RSO’s and things like that in the Black University. Big shout out to the Writing and Thinking Society. I’m the president. I’m joking. We’ve been having lots of conversations about the decline of intellectualism.

What was that one article that was in the Maroon Tiger that we read a while back about that? We’ve had lots of conversations about how our education here at Morehouse College isn’t as radical as we would like it to be and growing opposed to the idea of the Black University. We’ve been abandoning it. The idea that maybe the Credos job could be to create communities like the Writing and Thinking Society, where we can have these conversations and educate ourselves about these things that Morehouse may not want to be a part of its core curriculum because it’s too radical, because it’s not good for business or whatever the case may be. Moving Morehouse more towards the Black University could just look like creating incentives for organizations like that.

Isaac Dia

I’ll say for me, the one that I know about is with the Poetry Club at Morehouse. They also do prison education, but they do it through writing and poetry. What I think is more of an issue is events like the one I had in a Chinese literature class, where the speaker came in from Asia and she was telling us her life story alongside her writing and everything. There’s like so many events like that, like the poetry one, where we had inmates come, the ones they had been teaching, they came and performed a show where they showed us all the poetry they’ve been working on.

When we have those important community events, Morehouse will never tell you because, I guess, they just don’t care. When you get an email from the school or you get an email from Handshake or an advisor, all the emails that they spam you with are always filled with Goldman Sachs. I get ten Goldman Sachs emails a day, or Blackrock, Bank of America and Wells Fargo. I get a million emails all the time from those four people. Morehouse, as a school they have their obligations they have to meet, but I feel like they need to have more of a balance where it’s like, “yes, you’re here at school to get an education, to get a job.” To be a complete person, a complete human, you also need community, so here’s some more community type stuff. I think that’s where more of the issue with Morehouse comes. A lot of the stuff they’re talking about, like the Midnight Riot, I have never even heard about it before.

That’s why when you talk to a lot of students on campus and you tell them, “oh, yeah, I’m a part of this group, this organization,” or something, a lot of people are like, “oh, I had never heard about that before.” I think it’s more about getting more people to know about these programs because people want to do stuff.

I think the biggest issue is they just don’t know where to go to get things done.

John Greene

This is stuff we can do now, really. Even at the level that it is currently with the Credo, with Dr. Douglas controlling everything. If Dr. Douglas just wanted to say next semester, “come up with a list of things and have people vote on whether or not they want the Credo to be given out based on attendance at Midnight Riot clean up events or going to certain events we have at the Writing and Thinking Society.” These are things that are actionable even before we expand too much further.

William Saas

The morning panel was largely about public money. “The Black University and Community Currencies” was the name of the event. The afternoon consisted of two panels: one featuring yourself, Professor Douglas, and Camille Franklin from Community Movement Builders and Jared Ball from Morgan State University. In that first panel you talked about – I don’t know if we can call it a tension, it’s more than that – the incompatibility of the vision of the Black University with existing structures of higher education generally and more specifically, the HBCU (Historically Black Colleges & Universities). Immediately after that we had a conversation with students about the Credo. I’m asking you to go back a couple weeks now, but is there anything that you have thought since that day, since that meeting about the relative compatibility of something like the Credo with the Black University?

Isaac Dia

I think that the Credo can work with the Black University. I think that the only way the Black University can work is if you have a project like the Credo, because when you’re creating a Black University, if we’re going to use the Duboisian way – which I know, like Doctor Douglass loves to bring up – it’s all about being in community with the people around you. In order to have that community, you need to have a currency that can support that community. I think the Credo is the perfect way to do that. When the Black University is the one who’s issuing currency, when they’re the ones who hold the monetary power, we know that they can issue projects that will benefit the currency. They’re more likely to issue money that will benefit the community rather than a private bank who is profit-focused. This one is more community oriented and community driven. I think that when you have a real Duboisian Black University, they’ll just fundamentally come up with their own currency to help support their people because they realize they can’t rely on the US dollar or the federal system to support them in the ways that they need to be supported.

John Greene

I would say that the Black University is not something that could ever make money, in a capitalist sense. It’s even fundamentally opposed to the idea that its goal should be to fit into that structure. Its goal should be to envision something newer, to be a venue for new ideas separate from the current white capitalist, individualistic world that we currently live in.

I guess you could also say that it is fundamentally incompatible with something like the Credo because of what the Credo does to replicate the current capitalist system. You could also argue that the Credo is the perfect thing to allow for people to, whilst rebelling and envisioning something new, still survive and maintain their own lives whilst participating in this work that otherwise would not be able to make them money traditionally.

Isaac Dia

When you say the Credo replicates the capitalist system, I’m not sure I really understand. Do you think you could explain it?

John Greene

Just in that you’re taking the money and you’re working for it and you’re paying for it. There is the idea that there would be a private sector and the eventual goal, especially for the Credo to work in something like a Black University, you would probably need to get to the level we talked about, having it backed by the Fed or by the US dollar in some way. This wraps it around into being a form of capitalism and a different branch of the capitalist system, even if it would be more of a public money centered thing. It still would be fundamentally connected to the system that the Black University would be trying to disconnect itself from.

Andrew Douglas

I’ll just add, we didn’t get into Marx in the class, but Dubois, in his later years, turned Marxist. It depends on how far we take that critique of capital and the value form and the wage relation. I think your intuition, John, is moving in that direction. Even a kind of community controlled or designed and managed currency is still mobilizing commodified labor power and is still operating within the wage relation.

There are certainly critiques of the capitalist value form that would take issue with that. I think your intuition is kind of moving in a kind of conventional Marxist direction there.

John Greene

Yeah, I do agree with that, I think.

William Saas

Isaac, are you satisfied by John’s answer there?

Isaac Dia

Yeah, I understand the answer. I don’t think I agree with his outcome, but I definitely get where he’s coming from.

William Saas

On what grounds do you disagree?

Isaac Dia

I can see how, if the Credo were to continue in a traditional sense, we could end up with the same wage exploitation and capital relations that exist now, but since we’re using it in the Black University and the Black University is here for radical change, this gives us the opportunity to implement real change.

I think, if the Credo is actually to be used, we don’t have to tie it to the US dollar. That’s a way people get stuck; we don’t have to do the conventional thing anymore. We can branch out. If we really want to dismantle the system that’s going on, why would we then take our dollars to reintroduce them back to the US dollar, when we can use the Credo as its own form of currency?

We can get people to actually use that rather than US dollars. That’s just the way I was thinking about it. So that’s the only reason I disagree.

John Greene

That’s an issue that rears its head over and over again. To what degree should you be participating in the system to work against the system? Working within the system can often make it easier for you to sustain yourself and cast a broader net in whatever movement you’re building.

However, often you can end up being corrupted by the system and replicating the system versus attempting to do your own thing, which requires much more sacrifice. It will likely mean a lot less people will be involved in your movement – initially, at least – but can maintain some sort of purity, but what does that even mean if you don’t get anything done right?

Isaac Dia

Yeah. It sounds like we’re on the same page.

Bruce Malveaux

My question would be, how would you get people to use the Credo as a US dollar? What would the Credo be used for that the US dollar couldn’t be used for?

Isaac Dia

That’s always the toughest question. Getting people to use the Credo is something I talked about during the panel. If I gave you a dollar and if I gave you a Credo and I said, “hey, for the Credo, you have much more power in how you can spend it and how it’s invested,” I think more people would take that option over me just giving them a regular US dollar. If you were to really educate people on the power that they can have with the new money that we want to introduce into the world, I think they would be a little more accepting of the new dollar, the new Credo, rather than a traditional US dollar where they really don’t have much of a say in how it’s spent, how it’s used, or the value of it. If you tell somebody, “You can determine the value of the Credo,” like, let’s say one day you want to make one Credo worth five Credos instead of one Credo. Then, I think people will be down for an idea like that, when you can tell them, “You can get money for research with the Credos,” I think more people will be more willing to use it once they can understand the power that they can now hold from a more democratized currency. I think that’s how you get more people to use it.

Bruce Malveaux

Who will take the loss?

Isaac Dia

The currency issuer. Morehouse would take the loss if we were using the Black University as an example.

Andrew Douglas

I think what you’re speaking about, Isaac, is the power of monetary agency. Currently, as we’re sort of taught to think about how we use the US dollar, we don’t have a sense that we have any agency in its design, in its management, in its issuance. What we’re thinking about here is bringing a smaller local community together in a much more democratic way to exercise some agency over how that currency is issued, against what it’s issued, what kind of labor we want to try to mobilize, what sorts of things we want to invest in. Bruce, to your point, I think part of the idea behind this, anyway, is to get beyond some of the strictures of zero sum thinking, so that our instinct isn’t always to think about who’s going to take the loss, but to think about what we can do for one another through relationships of reciprocity, through relationships of give and take, democratizing those relationships in ways that are more mutually self-satisfying to participants in the process. I get where you go with that question of loss. We had some serious conversations in the classroom about how an institution, like a Morehouse, could afford to experiment with this complimentary currency given the fact that the institution and its business model and its legal status is still, by and large, beholden to the orthodoxy of the US dollar.

William Saas

This is great. Isaac in the panel, you very optimistically said the biggest benefit of the Credo project is the education that we can get from it. “We” being the students in the class. I think more broadly we’ve been talking about anyone who participates in such a project. You also kind of get a little bit more pointed and specific and suggest that the Credo assignment would be “fantastic,” your words, for the economics department. I want to suggest that, as an audience member, I found that to be intriguing for a couple of reasons. I think that would be pretty uncommon for an economics department. As you know, no doubt, from the kind of survey of neoclassical orthodoxy and mainstream economics that you would have gotten in your class, that many of them have no place for money in their syllabus.

In fact, money is kind of thought to be this thing that’s not that interesting. Why would they do it? I’m holding out that maybe the Morehouse economics department would be interested, but if you could expand on that comment, why would it be particularly good for economics departments to do it? Why might they be particularly receptive to an assignment related to developing and using a classroom currency?

Isaac Dia

My thinking behind why an economics department would really love a Credo was – this gets back to my main point – the education that the Credo can provide is almost unlimited. I’ve had to take macro and microeconomics as a course requirement for Morehouse.

When you’re learning about those concepts, kind of like how we do in political science, money is treated as a given. They just assume that this is how money works, this is what it is used for. We’re just going to show you the math behind it.

When I think about introducing the Credo, the student’s brain would explode and they’d be like, “oh, my goodness.” I, as an economist, now that I know there’s this thing called the finance franchise. The Fed uses interest rates and unemployment to regulate how much money is in the economy and the way that it’s used. The banks are issued money by them and the banks can create money on their own. This will show them that me, as an individual, will have a say in how money is used. Now I can take my knowledge, and I can go to a company like Goldman Sachs. I can even go to the government. We can have people who understand what money can do for them, and they can go into the system, like in government and the federal system, maybe they can even go to – if they really want to help take down the “evil capitalist,” quote unquote, they can go to like a Blackrock or Goldman Sachs and start applying the knowledge to help improve their communities.

William Saas

And you got the email addresses of Blackrock and Wells Fargo because the email you every day.

Isaac Dia

Oh yeah. Yeah.

John Greene

That kind of plays into the whole question of, “what is the goal of current education in economics?” Are they just educated to reproduce the current system? Would they be receptive to new ideas, like the Credo, that MMT are attempting to put onto the table?

The idea of monetary silencing, the idea that economics and politics have been brought to us as separate entities for so long and that one of the primary goals of MMT is to bring them back together again. To end this monetary silencing, to show that politics and economics are one in the same in many ways.

I think that would certainly be very interesting. I just don’t know if that is ever going to be the purpose of current economics as we know it.

Andrew Douglas

If I could just jump in here, my econ colleagues are wonderful, I love them to death. There’s only a handful of them. We’re a tiny college, right? I don’t think any of them really teach money regularly or certainly don’t specialize in monetary policy. I think that means, interestingly, there’s a lot of potential there. I don’t know that there’s going to be any kind of principled or committed pushback, necessarily. Part of what I’m interested in as a political scientist is thinking about money as a creature of law and politics and wrestling money away from economics as a discipline to some extent and anchoring it in political science as a discipline.

Realizing that all of these things are interdisciplinary. Money is an enormously and naturally interdependent and interdisciplinary sort of thing. The founder of our department here at Morehouse, Robert Brisbane, initiated political science instruction back in 1948. We have a thing called the Brisbane Institute that’s been moribund for a number of years.

I want to try to revitalize it and put the Credo project at the center. The purpose of that institute was to provide a kind of home for public facing, publicly engaged political science teaching and learning. It seems to me that the Credo project is an ideal project to relaunch that institute, tapping into some of the more aspirational dimensions of our mission: past, present and future.

William Saas

That’s incredibly exciting to hear. I didn’t know that. Did you talk about that in class, or is that that fresh?

John Greene

We talked about it a bit.

William Saas

Awesome. We have the Credo at Morehouse. Morehouse and its relation to the West End. What about Atlanta? Where does the Credo come in in the municipal city context of where you all live?

Andrew Douglas

This is something we talked about a bit in class, thinking about creating the demand for the currency as we scale it from a campus currency to potentially a community currency, and potentially to be something that could be used to pay staff, faculty, and students in wages. We’ve talked about appealing to the city of Atlanta to allow Credos to be used for city tax purposes, and appealing to the city to demonstrate its commitment to Morehouse, Spelman, Clark, and all the schools of the Atlanta University Center. They have long treasured these universities as these core Atlanta institutions. This would be a great way for the city to demonstrate its commitment to these institutions by agreeing to accept institutionally issued currency for city tax purposes.

Of course, that would go a long way toward creating a demand such that if people could use the Credo to pay their city taxes or at least a portion of it, they would be more willing to accept Credos as a portion of their wages. This is something we’ve talked about. I know, again, Benjamin Wilson, has been on Money on the Left talking about trying to experiment with this in Ithaca, and other places up in New York, but coming back to the point we mentioned earlier about a student driven bottom-up approach to this, nobody is more persuasive than the students themselves. If they approach the city council, the mayor’s office, the city reps with a proposal like this, I think it would be very hard for elected officials in the city of Atlanta to just shoot that down.

William Saas

We got some ambassadors for it on this call. That’s tremendously exciting to hear about as a prospect combined with the Brisbane Institute. It sounds like an amazing one-two-punch. We’ll have to have you back when that starts to roll out.

In the meantime, by way of closing, I know that Andrew has been at this for a couple of years, at least a few years, talking about public money in your classes. I’m interested in hearing about whether and how John, Isaac and Elijah have had occasion since taking the course to teach someone else about public money, to walk them through public money, MMT, and constitutional theory. What’s that been like?

Elijah Qualls

I have two different instances. When I was leaving Morehouse, I was on my way back to Ohio and my dad was driving me. It’s about an eight-hour drive. We were just kind of sitting and talking and I think my dad may end up listening to this podcast later on.

He’ll be the first one to tell you he’s very conservatively minded. A lot of his ideals go towards the right. When being presented with something like this, his immediate responses were to provide push back and ask questions transparently like, “How realistic do you think this is?

Do you really think this would actually work? Why would people want to buy into it?” Quite frankly, he was asking the same questions that our class was asking at the beginning of this semester. This is hard, especially coming from the public money lens, right? It’s not necessarily taking your concept of economics and turning it on its head, but it is significantly contradicting a lot of the concepts that we had already understood.

It was interesting to speak with him about it. In the end, he still didn’t buy into it, but I did not expect him to, of course. That was one instance. Also, talking to the student body at the workshop that we had. I don’t know if you had seen it, but during lunch there were a couple students who had come to my table, and I was explaining it to them.

It is a tough thing, in my first few interactions with it coming from Dr. Douglass, I still was struggling to buy into this whole notion, especially with MMT. I’m like, “what are you talking about, our taxes don’t actually go towards anything?” It’s a difficult thing because you’re socialized your entire life to understand that the roads you drive on, the freeways you take, and all the public entities that you enjoy are funded effectively by you.

If I understand MMT correctly, it takes that notion and retorts, “what your taxes serve to do is legitimize the US dollar and the public good that you enjoy could have been funded whether you paid taxes or not, in theory.” Right. I will say, even to those who are listening to this podcast now and they’re like, “this seems a little far fetched,” that’s a normal response. That’s how I responded. But it’s important to explore and leave no question unanswered. Ask all the questions you may have. When you do that, you begin to see the legitimacy behind the modern monetary theory and behind the public money concept. I think talking to the students and some family members about this has helped me gain a better understanding of the theory and see where it can apply and then what we can do with it, particularly, of course, looking at the “uni” project and the Credo.

John Greene

I have also explained it to my parents. I also have one friend who’s a super ultra mega liberal, and I’d be going back and forth with him and trying to turn him into a comrade. It never really goes well. I’ll have him on the ropes and then he’ll come back the next day, having refortified himself. One of the times we were talking, I was just like, “yeah, you know, the government prints money and taxpayer money is a myth” and all this MMT stuff.

I tried to take him through the whole thing and then eventually loop that back around to get him to agree and it didn’t work, but I think he was buying some of the MMT stuff at least.

Isaac Dia

Yeah. I’m a little luckier than Elijah and John. My parents, like my whole family are pretty tired of capitalism already. When I had told them, “There might be an alternative,” they’re just like, “hey, sign me up for it. You don’t even have to tell me. Just sign me up.”

I’ve been pretty lucky. I think the biggest challenge has been trying to incorporate a complementary currency in real life. I do stuff on the side. I have my own little organization in things I do. As a way to practice and see if this can work, I’ve tried to implement my own currency or where I’m not too focused on the dollar, exactly. If I need something, is there a way I can get it without having to exactly pay for it? I know it sounds like I’m stealing, but I promise I’m not. I just try and find an alternative to using the US dollar as much, and that’s been like a huge challenge for me. When you approach somebody and need camera equipment, I’m like, “hey, I know I need all this equipment from you. I don’t have money, but I can provide something else.” Trying to explain that to people and show them how it can be beneficial to them has been a challenge, but it’s something I’ve been working on in practice.

William Saas

What’s funny is that there are multiple ways to get things. Paying for them, straight-out, in US dollars is the easiest way. There’s a hierarchy here. You can also use a credit card. I’m not saying do that either. I’m saying that – and it came up in the panel and across the panels – there are alternative currencies that people use all the time to pay for things like airline miles, like credit card company points.

Well, I’ve certainly learned a lot, both through our conversation today and from your panel discussion. I want to thank each of you so much for your time today and for all of your deep and meaningful thinking about this very important and central question of monetary agency and of monetary design in our current moment of democratic turmoil.

Even if we weren’t where we are today, it would still be critically important for reasons that I think you spell out in your work. Thank you so much for joining us at Money on the Left.

John Greene

Thanks for your questions. It was a fun conversation.

Isaac Dia

Yeah. Thank you for having this. I enjoyed it.

* Thank you to Arya Glenn for production assistance, Robert Rusch for the episode graphic, Nahneen Kula for the theme tune, and Thomas Chaplin for the transcript.